Forgive the enormous, unwieldy, unwarned absence. It wasn’t out of simple unwillingness to go on, rather it was just that I was totally unable to think of anything to post about. Lord knows I don’t have tons of interesting things happening to myself, so my best bet is to tell you some of the random giblets of information that leak out of my skull and hope they don’t put you into a dyspeptic coma. Normally this leaves no end of room for topics, but I want to at least pretend I’m telling you something interesting, which whittles down my options. Then I take into account what I can comment on accurately with public-domain images, and that shaves my options right down. This is the reason you aren’t reading an article complaining about scientific inaccuracy in Jurassic Park, which, topically speaking, is like complaining about water being wet sixteen years after everybody and their mom was told this repeatedly by professionals.

Instead, once again, we will turn to those most (unjustly) loathed inhabitants of the watery bulk of our planet: the sharks. More specifically, we’ll be taking a look at the exact reason we’re all so antsy about them: the shark attack.

A shark attack in the good ol' days, when they apparently had lips.

As per usual in the discussion of the shark attack, it should be stated that you are more likely to die from a bee sting or lightning strike than a shark attack (except in Australia, where all three are apparently about equal odds). However, since bees and lightning don’t ascend without warning from the deep blue below to transform an innocent evening on the beach into a whirlwind nightmare with the fangs oh god the fangs I had a leg there a minute ago and so on, this seldom is very reassuring. Put more precisely: logic has no place in being scared witless. And since we already went over just how scary sharks and the ocean innately are, we won’t go through that again.

So, rare as they are, shark attacks happen. You put humans (LOTS of humans, nowadays) in a habitat that contains any number of naturally voracious, toothsome predators, and you’re going to have to expect a few incidents. However, most sharks aren’t really geared to think of us as food. Reef sharks love their fish, great hammerheads will go for a stingray without so much as a by-your-leave, and blue sharks enjoy a nice squid, but ungainly floppy mammal things have only become common elements of the sea over the past few thousand years, which isn’t a lot, evolutionarily speaking. Plus, we’re fairly largish. Although any shark has the potential and occasionally the motive to take a chunk out of one of us, the same could be said of nearly any creature on earth. If you’re looking for actual life-threatening injury, you narrow the long list of sharks (440+) down quite a lot – to the bigger fellows. The really dangerous ones out of this particular bunch are aggressive and/or grumpy (the bull), opportunistic (the tiger), or prone to hunting things that already resemble us to a degree (the great white). Given all this, it’s not surprising that shark attacks are rare, seeing as most sharks don’t have the motive or capability to go for us as prey.

So! Let’s take a look at shark attack types.

First, we’ve got the provoked attack.

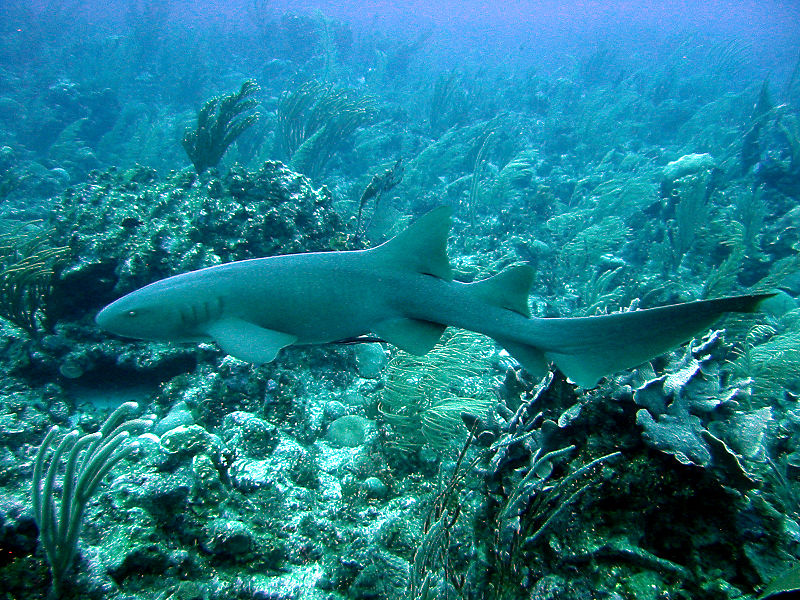

This blacktip reef shark is just not interested.

Sharks like their space, as can be seen by the aloofness of the blacktip reef shark (a common and very inoffensive little reef-dweller) above. They can get curious and poke things, but most species take offense when people stick their noses into their business, or, say, grab ahold of their tails.

“But random blogging person,” you say, “surely no one would be stupid enough to grab a shark’s tail!” And you would be wrong, says I, the random blogging person. See, there is a shark known as the nurse shark. It’s sluggish, slowish, medium-to-large (up to 14 ft) and eats some fish but mostly invertebrates – crustaceans and mollusks.

For a long time most books stated that it was fairly harmless and inoffensive. Now, what do you think ran through people’s heads when they heard this? Your choices are as follows:

- “Hmm, neat, guess I don’t have to panic if I see it.”

- “Hmm, neat, guess I can yank its tail and see what happens.”

Everyone who guessed the latter, you are winners. Everyone who guessed the former, you are optimists, and thus doomed to frequent disappointment.

"Inoffensive" is not equal to "will not bite you."

It turns out that nurse sharks don’t like having their tails pulled. It also turns out that those flattish, shell-crushing teeth of theirs, while not especially sharp, have a distressing tendency to bruisingly clamp onto things and not let go. Incidents like that of a young man who pulled a young (2-3 ft) nurse shark’s tail and had it attach itself to his chest until its removal at surgery would be classified as “provoked” attacks, or, more specifically, “stupid.”

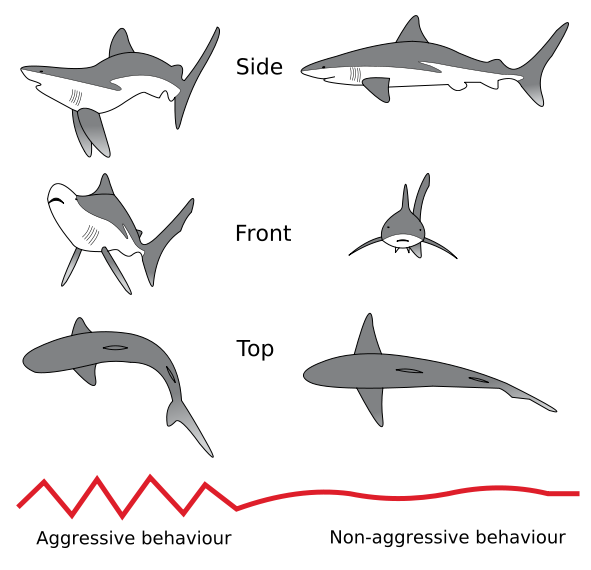

Provoked attacks most often result from the invasion of a shark’s personal space bubble, much like humans. Also like humans, sharks can share very different ideas on how big this bubble is. Quite a few species of reef sharks (most notably the grey reef shark) undertake distinct “threat behaviour” posture when they feel pressured: their swimming incorporates exaggerated movements and their backs hunch, putting them into an “S-shape.”

One of the first inklings people got of this behaviour was from a photographer who noted the posturing, was puzzled by it, and then was bitten by the shark on the camera, simultaneously gaining a valuable insight into selachian threat mechanisms and a bad case of the heebie-jeebies.

That’s unprovoked attacks. But where’s the sensationalism, the gore? Where’s the shrieking family members on the beach as a loved one is messily devoured two hundred feet offshore and forty feet down? Well, nowhere, to be honest, because real life isn’t usually like that. But let’s move on to the shark on the offense, striking out against the man: unprovoked attacks.

The International Shark Attack File recognizes three rough-n’-ready categories of unprovoked attacks by sharks. First, the most common: the hit-and-run.

A grey reef shark pondering a midday snack.

A hit-and-run attack usually happens when the shark and human involved are in crowded or turbulent conditions – like, say, crashing surf. The shark is probably noshing on some fish nearby, it sees the flash and flicker of silver scales in the water, it lunges – CHOMP – and hey surprise, it was some guy’s foot/shiny wristwatch/hand. Whups. The shark hastily beats it, leaving a confused and gashed swimmer/surfer/waterboarder/whoeverthehell in its wake. Most of the time the victim never sees the shark – unsurprisingly, as this encounter often hinges on the shark being unable to recognize the victim, and the shark usually has superior vision in the water. Sometimes it could be the shark requesting the human to get away from it, or showing the human who’s boss. In addition to being by far the most common attack, the hit-and-run is the most survivable and the most likely to produce fairly minor wounds.

The other two categories are much rarer and more dangerous. First up is the bump-and-bite.

An oceanic whitetip: grumpy and probably homicidal, but thankfully a mid-ocean roamer.

Whereas a hit-and-run is the heat of the moment, mistaken identity, or a dominance show, the bump-and-bite is more what you could call premeditated assault. The shark circles the intended target to take a good, long look at it, scoping it out from all sides. It might swim right up to you and poke you with its nose – the “bump.” Then comes the bite. This seems to be a good case of the shark taking a look at you, checking you out for food potential, and then following though on it with a deliberate attack – the classic image of a scary-ass shark attack. This also explains why it’s rare as hell, since, as mentioned previously, very few sharks are willing to think of you as food or something that needs killing.

Thirdly is the sneak attack.

A likely suspect.

As thankfully rare as the bump and bite, and just as dangerous, the sneak attack involves a massive, no-holds-barred blow from ambush – the modus operandi of the great white shark when seal-hunting. Similarly to the bump-and-bite, the attack isn’t usually a case of mistaken identity so much as a serious attempt to cause some damage.

Both the bump-and-bite and sneak attacks often occur in deeper water than the hit-and-run, and are far more likely to cause serious injury (de-limbment, massive abdominal chompings, etc) and outright death, and, completely unlike the hit-and-run, often involve multiple attacks. Any apparent tendency to engage in these sort of dangerous, prolonged assaults is what firmly paints a species on the list of highly hazardous sharks.

OH JESUS NOT AGAIN.

Highly hazardous to human life and limb, not mental stability.

All original material copyright Jamie Proctor, 2009.

Picture Credits (once again, all items located on Wikipedia):

- Watson and the Shark: 1778 Oil-on-canvas painting. Public domain.

- Snorkler with Blacktip Reef Shark: March 2006, Maldives, by Jan Derk. Public domain.

- Nurse Shark: November 22nd 2003, near Ambergris Caye, Belize, by Joseph Thomas. Public domain.

- Grey Reef Shark Threat Display Chart: Threat display of a grey reef shark. The postures become more exaggerated as the danger perceived by the shark increases. March 6, 2007, Chris_huh. Public domain.

- Grey Reef Shark: A grey reef shark photographed at Roatan, Honduras. January 1st, 2000, William Eburn.

- Oceanic Whitetip Shark: Carcharhinus longimanus, ca. 2.50m lang, Tiefe ca. 2-3m, mit Pilotbarschen (Naucrates ductor). Fotografiert am 09.06.2002 am Elphinstoneriff / Rotes Meer / Ägypten. Das Fotos wurde von mir selbst erstellt und ist im Originalzustand (also nicht bearbeitet). Weitere Fotos unter http://www.peter-koelbl.de

- Great White Shark: Photo by Terry Goss, copyright 2006. Taken at Isla Guadalupe, Mexico, August 2006. Shot with Nikon D70s in Ikelite housing, in natural light, approx 25fsw. Animal estimated at 11-12 feet in length, age unknown.

- Lolshark: Public domain basking shark photograph from Wikipedia, from NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center. Misshapen beyond all recall by the demon-haunted corruption of microsoft paint.