Apologies for the belated update.

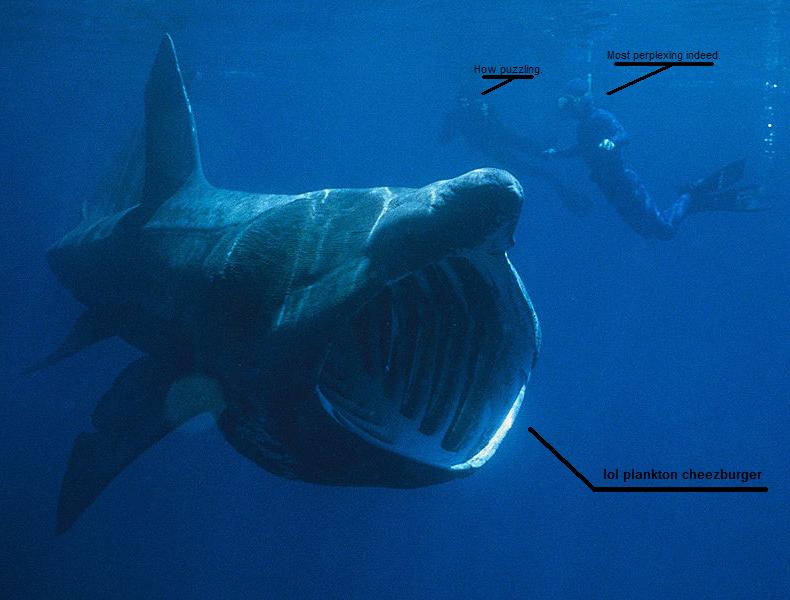

Once again, here I am, telling you stuff I know, often not very well. In keeping with the theme of the last post, the paltry, patchwork, and semi-inaccurate information that I impart to you will be related to those most humongous chunks of our planet, the oceans. Not in keeping with the theme of the last post, it will be about very large warships rather than very large selachians (cartilaginous fishes, or sharks and rays). Interestingly enough, the short bit of story I’m about to impart will contain nearly as many human casualties as the sum total of shark attacks included in the International Shark Attack File.

To emphasize just how casual and error-ridden this account will be, here is the casual and error-ridden guide to a clueless person’s ship categories that will be used in this account:

- Corvette: Tiny, nigh-worthless antisubmarine escort used to protect merchantship convoys. Canada built loads of ’em because that’s just how we roll.

- Destroyer: Not nearly as tiny, not nearly as worthless, and used primarily for similar duties.

- Cruiser: Now we’re getting somewhere. Decent-sized, but not in a battleship’s weight class.

- Heavy Cruiser: Cruiser that spent all of high school pumping iron and popping ‘roids.

- Battlecruiser: Like a battleship, but with less armor and more speed.

- Battleship: Hugeass, somewhat impractical, but much beloved by navies the world over until everyone realized at some point during WWII that aircraft carriers could smoke them completely from very long distances.

- Aircraft Carrier: A ship that carries aircraft, easily recognizable due to its flight deck. You probably guessed that already.

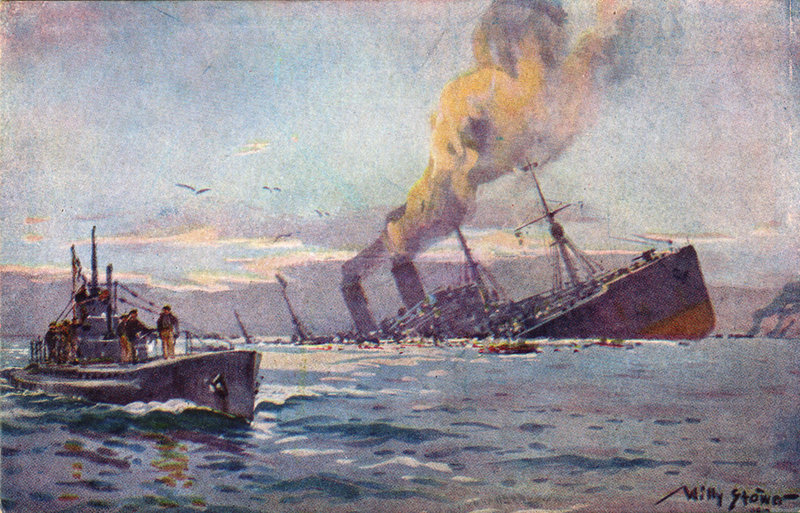

This tale begins, as so many things do, back in World War 2, when Germany was more focused on grabbing lebensraum than making excellent beer. By 1941 they’d seized most of Europe and were attempting to briskly throttle Britain into submission. The British Isles were much too small to support all the materials and goods their population required on their own, particularly food, and the going German strategy was to beat the living snot out of the convoys of merchant ships that made the trudge from Canada and the US over to British shores, delivering ammo, fuel, and food. German U-boats played a massive part in this: small, cheap submarines that spent the majority of their time on the surface, usually only submerging to evade and attack with torpedoes. Smaller warships such as corvettes and destroyers, armed with depth charges, helped fend off the attacks to a certain degree, but it was a back and forth struggle – particularly early on, when antisubmarine warfare was still fairly primitive.

There is nothing humorous about this picture, you callous prick.

However, apparently submarines weren’t manly enough for the Germans. Maybe it was because they were underhanded, sneaky, terrifyingly hard to spot, and highly effective. Thus surface ships remained a preoccupation of theirs for some time, despite the general advantage in size and scope that the British Royal Navy enjoyed. Besides, convoy raiding with battleships had a very appealing advantage: while a destroyer or corvette could seriously inconvenience a U-boat it cornered, a battleship was another story. Earlier attempts by the battlecruisers Sharnhorst and Gneisenau were encouraging, and eventually, in 1941, the Germans said “hell, why not” and set out the Bismarck.

Not actually the Bismarck.

The Bismarck was a behemoth, the third largest European battleship constructed in the war, behind only her sister ship Tirpitz (pictured above) and the British HMS Vanguard, which wasn’t complete before the war’s end. The Bismarck-class battleship was the third largest in history, just behind the US Iowa-class, which appeared several years later, and the Japanese Yamato-class, which appeared at around the same time and was best described in almost every dimension as “ginormous.” The plan was to ship out the Bismarck and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen up through the Baltic Sea to refuel in occupied Norway. From there on they’d strike out into the Atlantic by looping up and over Great Britain and Iceland, where they would meet up with the Sharnhorst and Gneisenau in the mid-Atlantic and blow up as many convoys as they’d like.

Right away, things started going to pot. The two battlecruisers were tied up with repair work. The Tirpitz wasn’t an acceptable replacement yet, so they could either wait or just shrug and press on without backup. The Germans opted for the latter, and set off. Unfortunately, they’d completely underestimated the paranoia of the British, who’d scraped up every battleship, battlecruiser, cruiser, aircraft carrier, and destroyer they could spare, and a few they couldn’t. They knew the Bismarck existed, and they knew when it set out. They also knew exactly what it was up to. In fact, the only thing they couldn’t figure out for quite some time was exactly where the hell it was.

Passing through Norway, Bismarck was the victim of what hindsight would reveal to be an extremely pointless and dangerous mistake. Her commander, Admiral Lütjens, opted not to refuel. The Prinz Eugen did so happily, topping up in the port of Bergen while Bismarck hovered. They then set off once more, having delayed for a full day (thus giving the British more time to find them) and preempting the possibility of hooking up with a prescheduled oil tanker a day or so north that would’ve been more than ready to fill up both ships anyways. Yes, this would come back to bite them in the ass.

The British, meanwhile, figured out that Bismarck and friends had recently visited Bergen, had it bombed one day late, and sent the Home Fleet out all over the place. As the German vessels moseyed their way through the Denmark Strait between Iceland and Greenland, two British cruishers, the Suffolk and the Norfolk, found them with radar. A few shots were passed before the massively outgunned and much smaller cruisers could scarper into the fog and pace them from a distance, keeping tabs on their position. It paid off. Some time later, as the Germans left the strait, they picked up other ships on radar. There were two: the freshly constructed British battleship the Prince of Wales, and a much more renowned vessel: the British battlecruiser Hood.

The Hood in its "hood," or possibly its "crib." Note attitude of relaxedness.

The Hood had been the pride of the Royal Navy for quite some time, and from the moment of its comission (1920) to the completion of the Bismarck (1940), it was the largest warship existing and pretty famous, something of an icon of Britain’s fleet. The Germans certainly knew of it, and probably were less favorably inclined. They were surprised to be confronted so immediately by capital ships, and that one of them was so widely known as formidable most likely didn’t improve their moods.

The Hood as seen by the Germans.

The four ships came into mutual range and promptly started shooting at each other. The Prince of Wales, being so new that it still had workers on it fiddling with bits, promptly began malfunctioning. The Prinz Eugen had been leading the way for the past while due to an error in the Bismarck’s forward radar, unknown to the British, and so they began to take shots at it, assuming it was the Bismarck. They realized their mistake fairly quickly, however, and after the first salvo started at the correct target. The Germans, meanwhile, focused their fire on the Hood.

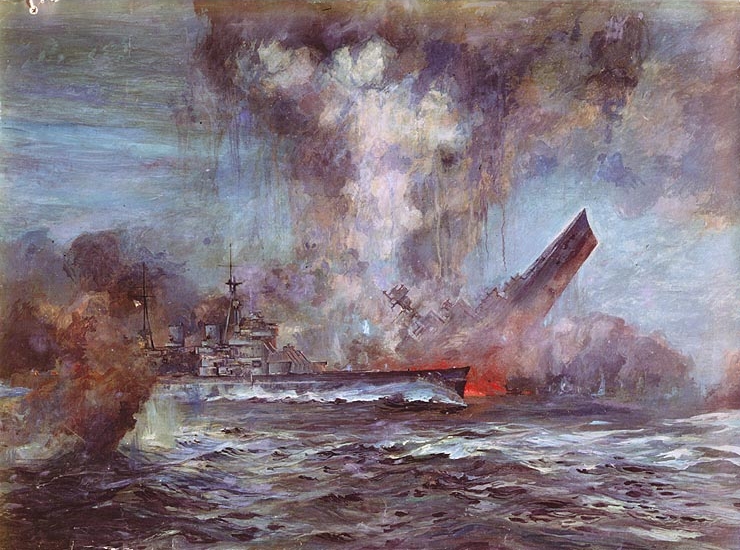

About ten minutes in, something happened. The commonly accepted theory is that one of Bismarck’s salvos landed amidships on the Hood and plunged through its somewhat thinly armoured upper deck. Directly into one of its magazines. You know, the locations where all of a warship’s ammunition is stored.

This isn't funny either.

From what’s said, the Hood simply exploded in two and sank immediately, along with one thousand, four hundred, and fifteen of its crew, leaving three survivors to be picked up by the British destroyer Electra.

Meanwhile, the Prince of Wales only had one working gun thanks to hits and general glitching, and was feeling several petals shy of rosy. Its commander wisely chose to get the hell out of there. Aboard the Bismarck there was general rejoicing, tempered with worry. Its forward radar was still screwed, the British knew exactly where they were and had probably become about five times angrier and more determined to see them sunk, and it had recieved several hits, probably from the Hood. At least one of the shots it had taken had caused a leak in its fuel, necessitating a speed reduction for conservation. Lütjens, probably feeling more than a little stupid about his wasted refuelling opportunity, told the Prinz Eugen to go on its way to fulfill the original mission purpose (convoy hunting), while he took the Bismarck down to dry-dock in occupied France for repairs. From there he’d be optimally placed to head out into the Atlantic again once the ship was patched up.

The British, now completely devoted to seeing the Bismarck to the bottom, promptly began throwing everything they had towards its position. First up to bat was the aircraft carrier Victorious. Unfortunately, all it had for planes was outdated Swordfish biplanes, each armed with a single torpedo. Every single shot launched at the ship from the little planes missed but one, which killed exactly one crewmember and caused damage best summed up as “superficial” to Bismarck‘s heavy armour. The attack as a whole, however, resulted in some loosening of anti-flooding blockage, causing the bow to sink down and necessitating further speed reduction until the repairs were reapplied.

Now becoming seriously annoyed by British tracking, the Bismarck took a drastic change in course, swerving around to the south and east and escaping British contact completely for four hours. Lütjens, possibly feeling that he hadn’t done his ship any crippling disfavours recently, thought he was still being followed and sent a message to home that the British promptly intercepted and used to give themselves a rough idea of where the hell he was. Unfortunately, the closest pursuer at the time, the battleship King George V, veered too far north in pursuit and gave Bismarck time to scarper.

Luck was on their side, however. In mid-morning, a reconnaissance aircraft spotted the oil slick left by the wounded Bismarck. Somewhat less warming news, however, was that the ship was heading straight for France, and would likely be within the range of cover that could be provided by German aircraft soon. If it was going to be caught, it would have to be slowed down drastically, and the nearest British ships were Force H, a group consisting of the aircraft carrier Ark Royal, the elderly battlecruiser Renown, and the cruiser Sheffield.

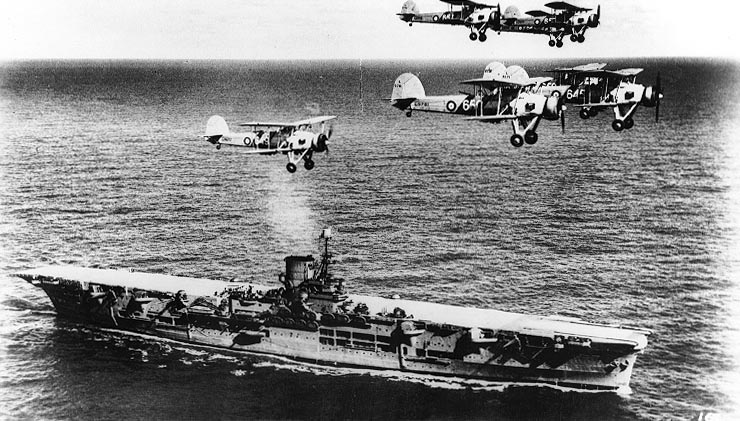

The Ark Royal, with a few of its little friends.

The Ark Royal launched its Swordfish, which unfortunately mistook the Sheffield for the Bismarck (which it was trailing) and launched torpedoes at it. On the upside, the Sheffield wasn’t damaged (all but one torpedo missed) and the pilots said they were really, really sorry. On the downside, the one torpedo that hit had failed to explode because its magnetic detonators were worthless. The Swordfish were recalled, fitted out with contact-detonator torpedoes, and sent out with a stern warning not to do that sort of thing again.

A Swordfish whose pilot is REALLY SORRY.

That evening, round two began. This time the Swordfish found the right ship and shot everything they had. They also found out through trial and error that the antiaircraft guns on Bismarck couldn’t be made to aim below a certain angle, and if they came in with their plane’s wheels just scraping the tips of the waves they would be fairly protected from the majority of fire coming from the ship. Most of the torpedoes missed, several hit, and five Swordfish came home damaged, one so badly that it had to be scrapped. The few hits the Bismarck took were safely absorbed by its thickly armoured hull – bar one. One single torpedo, by sheer bloody-minded chance, had smacked into the one marginally weak spot in Bismarck’s armour: its rudder. Bismarck began to develop a list towards port, and, most significantly, its rudder was now jammed, preventing it from being steered.

Despite every effort made to fix it, the battleship began to slowly turn in a very large circle: right back into its pursuers.

That night, British destroyers harassed the Bismarck to exhaustion, launching torpedo after torpedo, none of which had any significant impact beyond that on German morale, which was now rock bottom. The destroyers themselves came out of their raiding with no casualties and minor damage. The next morning, the British assembled for a showdown: the King George V had arrived in company with the battleship Rodney and heavy cruisers Dorsetshire and Norfolk.

Bismarck under the gun.

The last battle was one-sided. Bismarck’s guns were still working (and focused on the older Rodney, perhaps hoping for a repeat of the Hood), but the list to port and inability to steer made her both a sitting duck and a poor shot. Within forty-five minutes, she wasn’t firing anymore. The British battleships continued to blast the ship, while the cruisers came in to launch point-blank torpedoes. Amazingly enough, the Bismarck‘s hull was still intact, and the ship appears to have been sunk only when the engineers declared it a lost cause and scuttled it. All of the survivors went into the water, where the Dorsetshire and one of the destroyers, the Maori, began to pluck them out of the ocean. Unfortunately, a U-boat alert was called, and the British hastily left the scene with only one hundred and ten crewmen recovered. The next morning, the German U-74 and Sachsenwald picked up five more. The remaining one thousand, nine hundred, and ninety-five crew of the Bismarck all died, some during the battle, but likely the majority in the cold and oil-covered water.

Survivors at the Dorsetshire.

The Prinz Eugen did not locate any merchant ships, and its main success was refuelling and returning to port in France. All but two of the nine refuelling and resupply vessels provided for the German operation were discovered and rounded up. The German navy, the Kriegsmarine, was rendered ineffectual in all operations in the North Atlantic involving surface ships until the end of the war, going back to the tried and true U-boats. The end casualties of the entire incident, the first and last operation that the Bismarck ever participated in, were this:

- One sunk battlecruiser: the HMS Hood, pride of the Royal Navy.

- One sunk battleship: the Bismarck, pride of the Kriegsmarine.

- Roughly three thousand, four hundred, and ten dead sailors; approximately one thousand, four hundred and ten the pride of Britain, one thousand, nine hundred, and ninety-five the pride of Germany.

The sheer number of chance occurances peppered throughout the entire incident was movie-like enough that it was made into a movie in 1960, titled Sink the Bismarck! I saw a bit of it when I was five or six and therefore much more interested in knowing things than I am now.

All original material copyright Jamie Proctor, 2009.

Picture Credits (all images found on Wikipedia):

- Painting of a U-boat attack: “Versenkung eines feindlichen bewaffneten Truppentransportdampfers durch deutsches U-Boot im Mittelmeer” by Willy Stower. Public domain.

- Picture of the Tirpitz: Photographed early in her career, probably in 1941.U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.Source: http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/images/h59000/h59655.jpg. Public domain.

- Picture of the Hood: British battlecruiser HMS Hood circa 1932 while fitted with an aircraft catapult aft, taken from the U.S. Naval Historical Center. Public domain.

- Altered picture of the Hood: As above, but prey to the abomination of Microsoft Paint.

- Painting of the sinking of the Hood: Sinking of HMS Hood. Painting by J.C. Schmitz-Westerholt, depicting Hood’s loss during her engagement with the German battleship Bismarck on 24 May 1941. HMS Prince of Wales is in the foreground. Courtesy of the U.S. Army Chief of Military History. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph. Source: http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/events/wwii-atl/batlt-41/bismk-c3.htm. Public domain.

- Picture of the Ark Royal and Swordfish: Photo # NH 85716 British aircraft carrier Ark Royal with a flight of “Swordfish” overhead, circa 1939. Source: http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/images/h85000/h85716c.htm. Public domain.

- Picture of Swordfish: A Fairey Swordfish from the aircraft carrier HMS ARK ROYAL returns at low level over the sea after making a torpedo attack on the German battleship BISMARCK. IWMCollections IWM Photo No.: A 4100. May 1941. Beadell, S J (Lt) Royal Navy official photographer. Public domain.

- Picture of Bismarck’s final battle: The Final Battle , 27 May 1941. Surrounded by shell splashes Bismarck burns on the horizon. Photo taken during World War 2. Photograph published in: The Bismarck, Robert Jackson, Weapons of War, 2002, ISBN 1-86227-173-9. Photographer not identified, so UK Copyright contended to have lapsed 50 years after publication. Public domain.

- Picture of Bismarck survivors: Survivors from the BISMARCK are pulled aboard HMS DORSETSHIRE on 27 May 1941. IWMCollections IWM Photo No.: ZZZ 3130C. 27 May 1941. Royal Navy official photographer. Public domain.