Once again, it’s time to talk about people. This time, however, we’re going to do so under the aegis (delicious greek word) of physical/biological anthropology. We’re going to go check out the hominids in general. As per usual, I warn you that I’m not an expert and not only could you not take this information to the bank but you probably shouldn’t put it in your piggy bank either. Even inside a sock hidden under your mattress is a bit suspect. That said, here we goooo….

Mom, where do humans come from?

Why from the depths of time, Jimmy. Hah, just kidding. Humanity’s origins are barely from the very tip of the peak of the crest of the gently moving wave of the surface of the kiddy pool of time. We are latecomers and we are by here by chance, same as anyone else. Presumably, like almost every species ever, we’ll also soon be extinct. Them’s the breaks.

Annnnyways, our first appearances as a group (hominids) distinct from the rest of the primates show up around 6-7 million years ago, when our ancestors and chimpanzee ancestors split off from one another. Maybe someone said something they shouldn’t have in the heat of the moment, and if it weren’t for one mouthy simian, evolution’s course would’ve altered. Whatever. Anyways, after this follows a neat and linear progression of steady improvement from primitive ancestors to modern-day oh who am I kidding. Human evolution is a MESS, and our evolutionary tree looks more like a briar patch. Entire clans of anthropologists have vanished into it and never returned, and sometimes others come back changed and haunted by memories of seeing their colleagues torn limb from limb by rampant taxonomy.

The oldest thing we have that’s possibly a hominid (some people are arguing it’s too ape-ish) is Sahelanthropus tchadensis from Chad, dating back to the 6-7 mya (million years ago) limit or around then. We’ve got his noggin, some teeth, and five chunks of jaw. Maybe he was in a barfight. From then on we move into a gradually more and more tangled mess. We’ve got Ardipithecus ramidus from around 4.5 mya in Ethiopia, Australopithecus anamensis from roughly 4.1 mya near Lake Turkana in Kenya, and Australopithecus afarensis from 3 mya in Ethiopia and Tanzania (the species to which the famous fossil dubbed “Lucy” after the Beatles song belongs to). This last one comes with a twofer of confusion, where some of them are around five foot and 150 pounds and others are 3.5-4 foot tall, most likely from sexual dimorphism (the differing of shape between sexes in a species, most often in terms of size). This can only add to the trouble of identifying what the hell species some random jaw fragment you found belongs to.

Past about 3 mya afarensis‘s descendants started to split up further, making things even more annoying. You got the Australopithecus africanus of south Africa and 3 mya, the A. garhi from around 2.5 mya, and the more robust bunch of A. aethiopicus, boisei, and robustus from 3-1 mya around east and south Africa. Somewhere in this thicket is our ancestor. Or maybe we haven’t found him yet. Whichever.

Humanity Rhymes With Mundanity

Around 2-1.8 mya the genus Homo appears in its early forms. Bigger brains, smaller jaws and teeth, more dexterous hands, and diminished sexual dimorphism are its trademarks, along with the first stone tools (mastering the innovative and appealing idea of “smack chips off a rock, then take the chips and cut shit up,” leading into the Oldowan, the oldest form of stone tool industry).

Say hi to grandpa, kiddies. Hiiiii grandpa!

First up to the plate is Homo habilis, or “handy man.” Haven’t you ever noticed your plumber’s sloping cranium and pronounced brow ridge? If you have, you should probably phone an archaeologist somewhere. Dating back around 2 mya, this fella looked fairly similar to the good ol’ Australopithecines of ye olden dayes, but with a slightly less apelike skull. Apparently he still ate lots of fruit, but was more than willing to scavenge meat (whether or not they actually hunted is up in the air verging on not likely). He was walking upright and had a very strong hand – good for grasping and climbing, not quite so hot at fine manipulation, but still very precise and useful in toolmaking. Females were still probably shrimps compared to the big boys, and his larynx hadn’t descended yet – a process that begins around 1.5 mya with H. erectus and finished around 300,000 years ago, allowing complex speech and the uniquely human ability to choke on your own food. Thanks to the mess of our history, by the by, H. habilis may contain two or more early Homo species. Just in case you thought this was starting to become sensible.

Java man: unrelated to coffee or scripting.

After H. habilis came Homo erectus (“upright man”), whose name makes my filthy-minded sister snigger constantly. Pervert. Anyways, he showed up around 1.9 mya and celebrated the occasion by spreading around like crazy, starting out in eastern Africa and ending up in southeast Asia by 1.8 mya, probably motivated by the Sahara getting dry as a bone, forcing them northwards and outwards across the planet. Like habilis, erectus may or may not include a few species lumped together, such as H. ergaster, which it may in fact be a subspecies of. Or H. ergaster may be a subspecies of erectus. Or not. Look, it’s complicated, all right? Whatever their relationship, by a million years ago they were pretty much the last hominids standing, from a 1.6 mya pre-Ice Age population of five or sixish species. Being bigger may have helped.

Erectus and co were larger, less prone to sexual dimorphism, and in general much more similar to modern humans in overall proportions (probably less hairy than their predecessors, too). They had pretty fancy brow ridges still, but they had a cool 750 cubic centimetre brain size – an improvement over the 600-700 cc size of habilis, and one that shaped their skulls quite differently. They used it, too – fire shows up in east Africa nearly two million years ago, tamed fire in south Africa and the Kenya Rift Valley around 1.6 mya, opening up many diferent food sources, protection, and hunting. Stone tools were getting more and more complicated, even in Asia, where stone tools are slightly rarer because the locals sensibly used bamboo for many things (lightweight, strong, sharpenable…what more do you want?). Flaked hand axes, wooden spears, and scrapers for wood and skinning all show up, and a specific form of hand axe technology covering Africa, Europe, and parts of Asia is termed Acheulian. It was the greatest thing since chipped rocks, and more specifically, the Oldowan. Big-game hunting was helped along by both the bigger bodies and the nasty new toys, and horses, rhinoceros, bison, deer, and bears were all brought down in various locations.

Enter the Most Ironic Scientific Name Ever Conceived, Plus, Uncle Ned

Anyways, around 250,000 years ago (woah, what happened to millions?), archaic versions of Homo sapiens (“wise man”….ostensibly) show up. But we don’t have the scenery to ourselves for long. Another Homo offshoot sprouts up, the eminently cold-adapted and robust Homo neanderthalensis (or Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, depending on whether or not you think they’re a subspecies of us or just very close relatives), or the Neanderthal (if you want to be very German, as you would due to his bones being found in the Neander Valley, pronounce it “Neandertal”).

Your cousin Julie, twenty thousand times removed on your mom's side.

Neanderthals were by far the most similar to us of all our relatives, which made their differences all the more notable. They stood about five foot on average, were built robust (think dwarves – hugely strong bones with massive muscle attachments), had almost no chins, brow ridges, receding foreheads, projected faces, and brains that seem to be slightly larger than our own. Needless to say, explaining why we’re still around and they aren’t has always been an interesting affair. They were built for the cold, and did pretty well in Ice Age Europe. The stone tool industry termed Mousterian is heavily associated with them, and was quite an improvement over the old Acheulian hand axes – the same pound of flint that could make two nice hand axes could be turned into more than 30 inches’ worth of Mousterian cutting-flakes, using “prepared cores” of flint to create perfect surfaces to strike sharpened flakes from. It was also hard as hell; there are probably about twenty modern flint knappers that can approximate some of its tricks (“Levallois technique,” anyone?) as well as its creators did. Stone tools ain’t no game for kids.

Neanderthals buried their dead at least occasionally, ate one another now and then (reasons unknown), and seem to have occasionally left items in burials like red ocher powder and goat horns, pointing at some sort of symbolism. Who hasn’t done all of those things at least once, I say. Anyways, they were all gone by about 22,000 BC. Whether we outcompeted them, killed ’em off, or absorbed them is up in the air, although genetics testing says the last option’s probably not very likely beyond limited hanky-panky. Also, given our historic attitude towards things even marginally different from us (“Your skin is weird! WAAAAAAAAAAAUGH!“), I think I know where I place my money.

Yes, we sent porn into space. Just in case.

Well, what else is there to say? Homo sapiens either showed up in Africa and spread out like crazy (the “out of Africa” theory, a la erectus) or H. erectus populations worldwide gradually evolved into first archaic H. sapiens, then modern humans (the “multiregional model”). The latter option feels uncomfortably racist (“This uncivilized lot probably only became modern in the past millennium!“) and also has to deal with the issue that African populations have the most diverse types of mitochondrial DNA of anywhere on the planet, which fits nicely into the idea that we’ve been living there longer than anywhere else – which is confirmed by African finds showing modern features earlier than anywhere else on Earth. Don’t think we’ve gotten out of the confusion yet, though – human distribution patterns worldwide make no sense more often than not (“How did we manage to colonize Australia 45,000 years ago again, thousands of years before good boats?“) and there’s more than plenty to argue about.

The rest of history after this is a long and cloudy series of people stabbing each other repeatedly and building statues.

Original material copyright 2009, Jamie Proctor.

- Picture Credits:

- Australopithecus africanus sculpture: crafted by Toni Wirts, public domain picture from Wikipedia. Cruellly vandalized in Paint by yours truly.

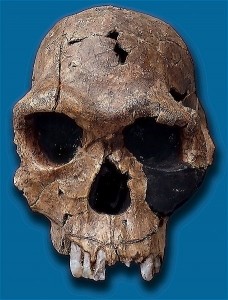

- Skull KNM ER 1813: picture taken by José-Manuel Benito Álvarez, 2007, public domain image from Wikipedia.

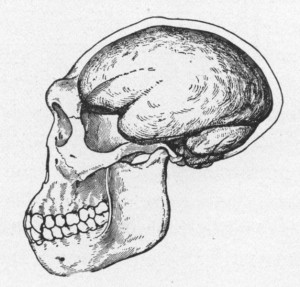

- Illustration of Java Man’s skull: drawn by J. H. McGregor in 1923, public domain image from wikipedia.

- Reconstruction of Neanderthal child: “Some people claim that this image is “incredibly human.” However, according to Christoph P.E. Zollikofer, it was made using modern techniques of computer-assisted paleoanthropology from the Gibraltar 2 Neanderthal specimen discovered by en:Dorothy Garrod at Devil’s Tower, en:Gibraltar in 1926. Tomographic scanning was used to convert the remains into a computer model, from which a physical model was constructed using a stereolithography apparatus. Soft tissue was then extrapolated using a thin plate splining technique originated in 1991.When distributing this image, provide a link to Anthropological Institute, University of Zürich as a courtesy to them.” Public domain image from Wikipedia.

- Depiction of man and woman from the Pioneer’s plaque: Public domain image from Wikipedia.