I am beset by doldrums of implacable size.

Colonel Thomas P. Fiddlegate stared at the sentence he had just scribbled, and found that it was so apt that he had no energy to press onwards. His eyelids felt like lead, his limbs iron, his mind a stone. Also, he was over seventy. That was probably the worst bit.

“Pinfat, my friend,” he somberly addressed his servant, as he tossed his journal to his desk, “I am altogether through. Finished. What is there left in life for me?”

“Lunch, sir,” said his servant. “And my name is not Pinfat, it is Paul. Pinfat is your cat, who is presently occupying your lap.”

“What greater purpose, Pinfat?” continued the Colonel, ignoring the noises of the underclass with Victorian ease as he stroked his cat. He eyed the majestic, weather-beaten globe atop his desk with grim displeasure. “What prime mover that shall shape my life and fortunes? I have done all that there is to be done, have I not? Have I not also seen all that I might see? I am rudderless!”

“It was just a little clam, sir. Hardly the end of the world.”

Colonel Fiddlegate’s moustache made the best effort at bristling that it could, though frightfully undernourished. “Just a clam?” he muttered in disbelief at the gall of servants. “JUST? Pinfat, that clam was the last of its family in all of Africa I had not hunted, and with that, the last of all clams in Africa I had not pursued, and with that, the last of all clams in all the world that I have not laid bare claim to! Pinfat, I am FINISHED! I am DONE! I am altogether THROUGH with clams now!” He stomped his foot firmly on the floor, causing Pinfat to bite him toothlessly in protest. “Only one clam left in all the world unseen by these faded old eyes, and that one a myth, I made sure of it!”

“Congratulations, sir.”

Fiddlegate slumped. “I am pointless without clams, Pinfat! Whatever will I do? What can I do?”

“Look to your peers for example, sir. Perhaps your brothers.”

“I’m intolerably poor at cards, Pinfat. And gambling is an acid of the soul.”

“The scotch, then.”

“No, I’d drain the bottle. I’ll take my misery in sober silence, thank you very much.”

Paul left the bottle. After about an hour, he came back and retrieved it for the garbage, leaving an extremely battered and cat-furred blanket to keep his master’s scrawny kneecaps warm against the cold. And so went the evening of Colonel Fiddlegate, who had killed all of one man during his glorious forty-year career (inadvertently: he could’ve sworn that the oyster he’d offered his sergeant was a good one, and nobody had ever argued differently).

Evening wore on, grew threadbare, and dissolved into night.

And in that night, came the dreams. Most were nonsensical. Some were anecdotal. And one, one was inspirational.

“AUSTRALIA!” bellowed Colonel Fiddlegate, starting upright in a fit and causing Pinfat to cling to his legs with the agility of a squirrel. “Ow,” he added, and hastily scooped up the paralyzed cat. “Australia!” he whispered to its surly face. “There! That’s where I’ll find it! I never looked for it there!” His eyes turned to the globe on his desk again, this time filled with hungry fire. “Australia!”

“You hollered, sir?” asked Paul. “It’s nigh-on five in the morning.”

“Fudge to the hour Peter, fetch me my bags!” ordered the Colonel, leaping to one foot and then with some difficulty to the other. “We’re off to terra incognita! The lost continent! The land of the kangaroo and the emu-bird! The Last Clam, the Myth-That-Burrows, the Hidden Pearl – it’s got to be there! I’m sure of it! The one place I never looked! Australia!”

“That is a most strenuous voyage to make at your age,” opined Paul. “And my name is not Peter, sir, it is Paul. Peter is your brother-in-law who passed away three springs ago, god rest his soul.”

“Bah, the devil himself would’ve been hard-pressed to squeeze a drop out of him. He’ll be fine! And Peter, don’t worry your head about me. I’ve made worse voyages and longer treks in my time, in my time with you, and with all the other years between! Remind me to tell you a few of those stories.”

“Were there clams involved?”

“Indisputably,” mused the Colonel, as he patted down his sides for his notebook. “Indisputably.”

The air was as fresh as the waves were salt. Gulls cried out in greeting to the ship, surprised once again to see such a large, wooden gull that sat so firmly upon the ocean. They were just gulls; it was hard to blame them for believing that sort of nonsense, especially when it was doing such a lively job of regurgitation, presumably to feed its young.

“It is indisputable,” Paul noted, “that you are ill.”

“Just a bit under the weather, that’s all,” mumbled the Colonel through a mouthful of unspeakable fluids never meant to touch human lips. He coughed damply. “This boat moves far too quickly up and down and not nearly fast enough forwards. How long have we been out here at sea? No, wait! Don’t tell me! Oh lord I wish to walk the land once again, to find the Hidden Pearl’s soulful-smooth shell beneath my fingers. There’s barely any details on it, you know – just whispers on the wind, between errant lips. They speak of what it is, but not WHERE, never where. Oh lord, I must walk!”

“Courage, the shore’s in sight. Australia awaits, much to the displeasure of your cat. I believe he has grown used to feeding upon the rats of the hold.”

“Thank the lord and every single one of his guppies,” whispered the Colonel. “Let Pinfat moan as he will; I feel better already. Haven’t felt wind of an illness like that since I went after the Coughing-Clam of Peru. Did I tell you about that one?”

“No, sir. You were busy vomiting.”

“Ah. So I was.”

“About this clam, sir?”

“Yes! The Coughing-Clam! That was a tricky one. Very easy to find, you see – when it coughs, it spits up a great big trail of bubbles. You can track them through any streambed with naught but your wits and a magnifying-glass, and in a pinch a keen eye substitutes for free!”

“Impressive.”

“Of course, I didn’t have a keen eye, but after I dropped my glass into the stream I learned to make do.” The Colonel broke into a shuddering dry heave, but more out of habit than anything else. “But anyways, Peabody, the hard bit wasn’t the finding. No, no, no. The hard bit was the CATCHING.”

“How so? And my name is not Peabody, sir, it is Paul. Peabody was your nurse as a child, who once tanned your hide near to the bone for playing in the chimney and getting soot all over the carpet.”

“The catching, you see, it’s the catching,” the Colonel continued. “Oh, it looks easy at first – just any old clam, eh? Grab ahold, yank ‘er up. Except it turns out the Coughing Clam can holler with such force underwater, Peabody, that it can numb the fingers and paralyze fine muscles. Trying to pick one up with tongs is no great shakes either; the force transmits up the tines, you see. I nearly shook my hands to pieces seizing one. Finally had to kick the damned thing free and onto the shore – no easy work, that, given how firmly they wedge themselves into the mountain streambeds – and even in the open air it made my hairs stand on end just having the thing wrapped in canvas in my backpack. My left pinky never did stop shaking, Peabody – not to this very day! Not now, even – see?”

Paul saw. “That’s just from the stress of vomiting, sir,” he opined.

“Possibly,” admitted the Colonel. “Excuse me a moment, one more for the road.” And he doubled over the railing again.

“Enjoying the road, sir?” asked Paul.

“Oh, damnably hot,” replied the Colonel, squinting at the nearer of the three horizons he could see, “but otherwise, yes, quite pleasant. I can almost see the shell of the Myth-That-Burrows before my eyes, even in this hellish heat-haze. It’s as if Helen of Troy herself stood before me – well, if she were a mollusk. Tell me, do you think you could ask one of those three fetching young ladies over there how much farther it is to Alice Springs? I feel quite light-headed, and a cool shade-nurtured drink would give me quite a rousing turnabout, I think.”

“There is only one lady, sir.”

“Oh?”

“Yes. And she is a camel.”

“Oh,” said the Colonel with a frown. He swayed a bit in his saddle, waking up Pinfat, who perched atop his shoulder. “Oh dear. I’m mad with the heat again, aren’t I, Paul?”

“Yes sir. Although you did just get my name right. Thank you.”

“Oh. Think nothing of it! Are you sure she’s a camel?”

“Yes. And technically sir, a he.”

“Oh. Oh my. Well then, nothing to be done for it but wait. We ARE close, are we not?”

“Within the hour.”

The Colonel slapped his hands together. “Time enough for a story then! Paul, did I ever tell you how I wrestled the Dread Anklecrusher of the Phillipines?”

“Not once, no,” admitted Paul. A faint spark of intrigue glimmered in his eye.

“A deficiency in your education!” proclaimed the Colonel. “This was all, you know, quite some time ago. Now that I think on it, probably before you were born.”

“Most of your stories are that way.”

“True, true. Anyways! This one was earlier in my career, you understand. I was still full of enough piss and vinegar that I thought nothing of haring off into the wide unknown on a rumor and a whisper of a clam to test my mettle!”

“As opposed to now, sir?”

“Precisely! So there I was, on the tiniest, least hospitable reef ever to host a human body. Sharks at every turn! Barracuda at my heels! Jagged, razor-edged coral lurking at every stroke! I’ve still got the scars, you know. My left buttock will never again resemble its youthful shape, alas.”

Paul coughed in that way that has nothing at all to do with clearing the speaker’s throat.

“Right, so I was on the reef. And I knew I was looking for a clam there in the shallows, but I didn’t know what kind it was. I estimated it was going to be about shin-high at best. You know, for crushing ankles and so on and so forth.”

“A logical assumption.”

“I thought so too. Unfortunately, it transpired that the Dread Anklecrusher starts at your ankles and works its way up to your neck.”

“Its rough dimensions, sir?”

The Colonel frowned and thumped his right ear, causing Pinfat to gum his neck in protest. “Can’t quite remember. I was awfully short of breath when those nice fishermen dragged me out of the sea, and I can’t really recall anything I did that year without it looking as though someone’d draped gauze over my eyes. But I was still clutching a fistful of the beasty’s innards in my right hand, and they said it’d probably expire within the week. So, hunt successful!”

“I’d always speculated on what was in that musty jar you keep at your bedside.”

“Well, yes. I figured it was probably good luck, you know? Tell me, have we reached Alice Springs yet?”

“We have indeed, sir.”

“Good, good. Ask that nice man for a drink, would you?”

“That’s the bar, sir. You’d best have a lay-down on the double.”

“Quite right, quite right. We’ll head to the springs tomorrow.”

The Colonel inspected the flat sand in front of him with faint suspicion. “Perdue? Where are my glasses?”

“At home on your desk, which we both lamented greatly over the day we set sail from England. And my name is not Perdue, sir, it is Paul. Perdue was your closest colleague in elementary school.”

“So he was, so he was,” agreed the Colonel. He frowned at his feet, which Pinfat was sitting on, having disdained the dirt as a bed. “Blast it. You’ll have to verify my eyes then: isn’t this supposed to be, well, the springs?”

“Alice Springs has no springs, sir. This is the Todd River.”

“Ah. But it has no water.”

“Astutely noted. The Todd River is dry almost entirely year-round, save for when heavy rainfall sends it trickling along its bed. The flood is quite sludgy, and can usually be outpaced at a reasonably brisk walk.”

“A brisk walk?”

“A walk might be overstating it. Perhaps a nimble amble.”

The Colonel sighed with displeasure. He half-heartedly booted Pinfat off his toes and onto the dirt, where the cat resigned himself to examining twigs and meowling crankily.

“Don’t fear, sir. The weather’s been poorly lately; perhaps the rains will come before we leave.”

“Before we leave?” The Colonel smiled sadly. “Perdue, how old am I again?”

“Modesty precludes my mentioning it, sir.”

“Speak up, man! Give me credit for a little temperance!”

“Ninety-three and one-half, sir.”

“Nearer to a century than to seventy-five. That’s not the sort of age one makes trips of this kind at, Perdue. Do you suppose I’ll survive another voyage on that… death-bucket?”

Paul didn’t say anything. Instead he provided a small flask of whiskey, which the Colonel drank.

“Thank you,” he said. “So! We wait. How long can we afford to wait? How long can I afford to wait? I’m not young anymore, Perdue. I can’t spend eight months here in the desert, like I did when I hunted the Mad Lurker of Morocco!”

“How exactly was this clam ‘mad’, sir? Surely clams behave in much the same manner, living or dead?”

“Oh-ho, not this one!” chuckled the Colonel. “Had the tale not passed to you? Surely I mentioned it?”

“Not in the slightest.”

“I shall remedy this then, if only to distract me from our present troubles. ‘Twas all back in the old days, when I was young – I think forty? Yes – and the world was new to me. Clams were but a word for something I ate as part of a seafood feast. I was barbarous, but I claim youth and ignorance as my defense.”

“Now, at the time I was in Morocco for… some reason or another. I can’t recall, wasn’t important. And I had, at the time, acquired an enormous ball of hashish through some sort of accident.”

“Accident?”

“Yes, I can’t quite recall, but I think it involved a few dogs, a game of cards, and someone having to leave in a hurry before their wife caught them. So here I was stuck with this MASSIVE ball of hashish. The question was what on earth to do with the damned thing. I couldn’t throw it away or someone would notice, I couldn’t turn it in to the authorities without raising awkward questions, and I couldn’t just hide it. Someone would be bound to find it, probably Parkinson. Your predecessor thrice removed, I believe, though much shorter than you.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“It’s just the truth, no need for formality. Nice man, Parkinson, but he could no more keep a secret than he could reach the top shelf of my whiskey cabinet. Anyways, the only thing to do was to ingest it. Which I rather foolishly did all at once, at night, on the shoreline.”

“I see.”

“So as not to be disturbed.”

“Indeed.”

“Now, my memory is difficult to sort out from my imagination hereafter –“

“Can’t imagine why.”

“-don’t interrupt, it’s terribly rude, you know. But yes, everything is a bit of a blur. I think I waded out into the waves at first to see if I could catch them, and then after about half an hour of THAT I decided I’d seen something shining on the seabed and decided to see if I could pick it up.”

“Oh?”

“Oh indeed. Indeed. And I had! Addled though I was, my eyes were keen back then. I reached down to that glimmering red-and-gold shape and plucked it up and it bit me, bit me hard and deep into my left index finger. Such a nasty shock! See here, you can see the mark – where the veins blacken.”

“Gruesome.”

“Oh yes. And that’s after fifty years; back then I believe it went bright purple and green very quickly. Now of course I grew very angry at this little nipping thing after that, so I did what any sensible person would’ve done.”

“Which was?”

“I stomped upon it. Wait, did I say sensible?”

“You did.”

“Scratch that from the record: I meant to say ‘damned stupid.’ It’s the reason I’ve had to wear extra-thick socks on my right foot at night the last fifteen years. I think something got into the bone down there, and it’s been eating away at it for decades now. Pretty fierce stuff in that clam. For that’s what it was! The Mad Lurker of Morocco – a shining little star in the sand that will nip you and fill you up to the brim with loony-juice if you dare touch it. Quite fatal, of course. Eventually. You run around like absolute bonkers for at least an hour before expiring.”

“And yet you sit before me living and breathing, sir.”

“With difficulty, yes,” admitted the Colonel. “This air is too thick with heat. But your point is made; I went quite mad, of course. Howling at the moon like a dog, barking like a seal, ran the streets like a bull… I even tried to eat the front door of my quarters. Lost a tooth doing that, which is why my smile is so golden these days. But I made it through the night, and the five-day hangover after that, and when I finally stumbled out of my bed and changed my clothing, what did I find in my pockets but the Mad Lurker of Morocco! Gave me a start, and made me glad I’d been out so long – a few days earlier and it might’ve still had enough fight in it to give me a second nip. And THAT would’ve put an end to me, for as everyone told me afterwards, all that saved my life was that hashish. It did something quite queer to that poison, and saved my life, albeit in one of the most miserably sickening ways I’ve ever experienced. If I close my eyes on a bad night, Perdue, I can still taste the fire and dirt on the back of my tongue.”

The air was quiet for an instant or three. Pinfat bristled his fur at some imaginary cat-nemesis and scuttled to his master’s shoulderblade with supple ease, ears twitching.

“And that was what made you decide to hunt clams?” asked Paul, breaking the silence.

“Hmmm?” replied the Colonel, dragged back half a century at once. “Oh, yes. All that pain and distress all caused by one tiny creature, and yet saved by such a slight sampling of the Lord’s favour. It was a sign, I thought, and all my life I’ve strived to live up to it. And that’s how it was. There, wasn’t that a pleasant distraction from the vast and groaning weight of my failures, Perdue?”

Paul stared at a fixed point on the horizon, and said nothing, though his hands twitched.

“Oh, blast it, I suppose it wasn’t. It feels heavier than ever! I am finished, Perdue! Absolutely done! Demolished! All the work and all the adventures and all the hunting and scraping and harm a body can stand, and all for naught – all for naught! A man can end happy knowing he’s collected every clam, but what can a man who claims all-but-one say for himself? It’s worse than having never started at all!”

“Sir,” managed Paul. “Sir. Would you care to look upwards, sir? To the north?

The Colonel slumped dejectedly. “Oh fudge to it, Perdue. You know I can’t see worth a half-pence without my glasses. Why, the clam itself could pop up right under my toes and I wouldn’t see worth spit.”

“Sir! The river!”

“Eh?”

“It’s coming!”

It took the Colonel some ten minutes to make out what was going on. This was good, because that was how long it took for the slow, sludge-driven, mud-choked Todd River’s currents to ooze their way to their feet, driven onwards by the relentless pressure of rainfall and gravity against a mouthful of grit and muck that would’ve throttled a less determined river dead in its cradle.

“My word,” said the Colonel. “I’ve never seen such a stream.”

“Very silty indeed, sir,” observed Paul.

“Ah, needs must! We’ll manage just fine – here, help me search the streambed, and mind your toes. I doubt crocodiles have had time to move in, but all the same, let’s be wary fellows and sing out if something grabs ahold of your legs, eh?”

“At once, sir,” said Paul. He gently removed Pinfat from the Colonel’s shoulders and placed the unresisting cat on the riverside. “One question: what exactly am I searching for?”

“I haven’t the faintest. Anything clam-like will do. Now scoot!”

The water was warm, despite its recent fall from the sky; the Australian soil was nearly half its bulk now, and had lent a sun-baked heat to it in addition to a chocolaty thickness. If Paul squinted his eyes just right, held his head at the right angle against the sun, and blinked rapidly, he could just barely see nothing at all.

“Go by feel, man!” called out the Colonel. He was bent double in the stream, groping about with fingers and toes. “Go by feel! We can’t be wasting time now!”

Paul did so, though he paused to roll up his sleeves first. “Sir, what do clams feel like?”

“Ridged!” shouted the Colonel, raising his voice over the rumble of the waters. “Patterned! Anything that’s too regular to be a stone! Look for-”

At the exact moment the Colonel’s voice subsided, Paul realized that the waters shouldn’t be rumbling when they were moving at a nimble amble. He looked up in alarm, and it was because of this that he managed to be standing upright when the entire Todd River tackled him in the midsection in a very slow, ambling, muddy way that drove him several hundred yards downstream and deposited him on a high bank, plastered with enough sediment to start an orchard.

Paul stared at the sky for a moment, reflecting dreamily that he now knew the meaning of Brown. His vision was Brown. His mouth was filled with Brown. His body was Brown. The entire world and everything in it made a little more sense now that he’d been through that. At least the bits of it that were brown.

He blinked, flicking mud from his eyelashes as he did so. There was something important. He needed to do something. For someone. Who. Whatever it was, he had the feeling it wasn’t Brown, and therefore was going to be difficult to cope with.

Pinfat came into his view, then sat on his head.

“COLONEL!” yelled Paul – with difficulty, emitting a good deal of Brownness from his lungs as he did so. He coughed viciously and bolted upright, fell over, then picked up the alarmed Pinfat and lurched desperately along the riverbank, legs dripping with Brown. “COLONEL!”

The Colonel was nearly a mile downstream. He was a much smaller man than Paul, and the flash flood had buoyed his bird-light bones along on the foaming crest of its waves, almost tenderly.

It was still too much, of course. Too much.

“Oh,” sighed the Colonel. “It’s you. Good.”

“I’m sorry, sir,” said Paul. He leaned down to pick the old man up, then stopped himself when he saw him wince. “Can you move?”

“Move. Uhm. Hmm. No, no I don’t think so. Maybe in a few minutes, but not right now. There’s something… rather… I think important. It needs doing, but I fear I can’t seem to move my hands. Coughing Clam seems to have caught up to them at last – or was it the Mad Lurker?” He coughed. “Bit stupid name for a clam, really. Not sure it was the right one at all.”

“Sir?” asked Paul. “What do you need?”

“Could you – would you mind – if you could just – grab my hand there, and pull it over. No, not over there. A bit up. Right. My right. Thank you. Now close my fingers.”

The Colonel’s eyes were hard to see under the mud, but the wrinkling of his face showed they’d just closed in satisfaction. Then they creaked opened again, with renewed purpose.

“Yes, that’s right. That’s right. Now please, can you please, would you please hold up my hand? A bit close, good fellow – my eyes, they aren’t what they were, I think. I can’t seem to see much now.” He peered closely. “That’s strange. It’s… browner than I expected.”

Paul leaned over and wiped the Colonel’s eyes clear with his pinky, as carefully as he could.

“Ah. Oh. My,” he said, and the drying mud cracked around his mouth as it spread into a smile, breaking free his shabby little moustache. “There it is.”

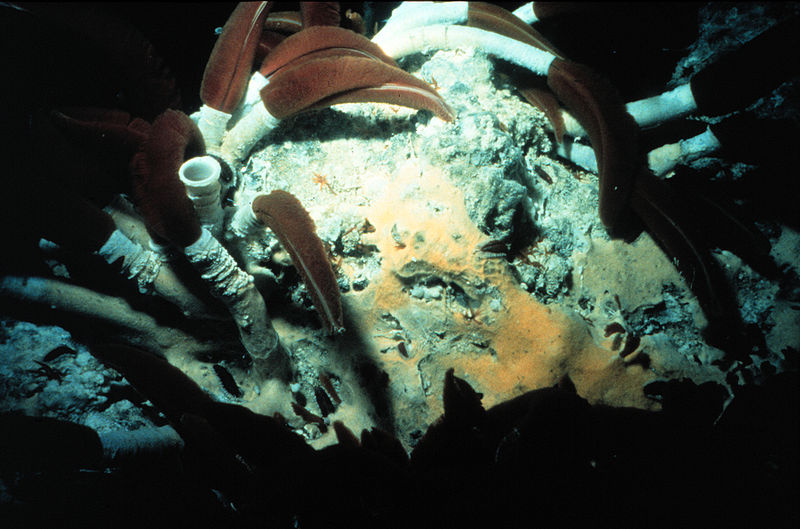

The shell was a mottled sort of brown-and-grey, where the greater Brown had not overcome it. It was just a bit smaller than the Colonel’s palm, and little bubbles were leaking from one end as the clam breathed.

“Now tell me, Paul,” said the Colonel, as his eyelids began to droop again, slowly but implacably, “have you ever seen a more beautiful thing?”