“But what’s left to say?” you might not ask, so I will ask myself for you. “We’ve already covered shark attacks, dangerous sharks, and several hideous photoshop’d lolsharks!” “Why, but the shark’s senses, Jamie,” I tell myself in the condescending voice I use for friends and relatives. “You should know about this already, you shallow and insufferable twit.” I laid myself out after this with an enthustiastic yet inept punch to my frail, porcelain-like jawbone, so I can’t recall the rest of that conversation and the following article may become incomprehensible in places where my brain damage in leakeds.

Electroreception

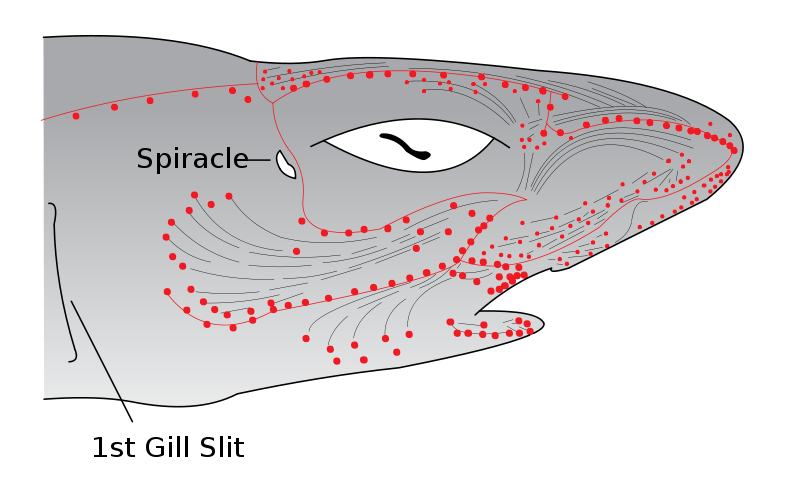

This chart, sadly, contains no pie. Imagine one for yourselves.

Since we’re going alphabetically, first up on the list of shark senses is one that we don’t have any equivilant for, because we suck. Jelly-filled tubes in a shark’s face (the Ampullae of Lorenzini, named after the guy who first really took a look at them in the 1700s) detect electrical fields in the water. How sensitive are they? They can detect muscle contractions. Go from this to the fact that the heart is a muscle, and if you’re close enough a shark will notice you based solely on your heartbeat. That’s pretty impressive, and in fact sharks may be the most electrically sensitive animals on the planet. It’s extremely possible that they also use the Ampullae to find their way around the world, sensing the planet’s magnetic field and electrical currents within the oceans – a useful trick for any species that wander around a lot.

Hearing

It'll hear you coming. But it only loves you for your spearfishing.

Shark hearing tends towards good. Higher-pitched noises give them difficulty, however – the upper registers of our hearing are completely soundless to them. Screw that crap. This is the ocean, not some namby-pamby surface world. We use LOW-PITCHED sounds here, and we like it, and sharks hear those like a cat hears a can opener. They can hear very low noises with incredible accuracy for several miles…. such as those emitted by something splashing into the water, or a fish struggling in distress. No, I’m not deliberately trying to add a sinister bent to each and every capability, why do you ask?

Sight

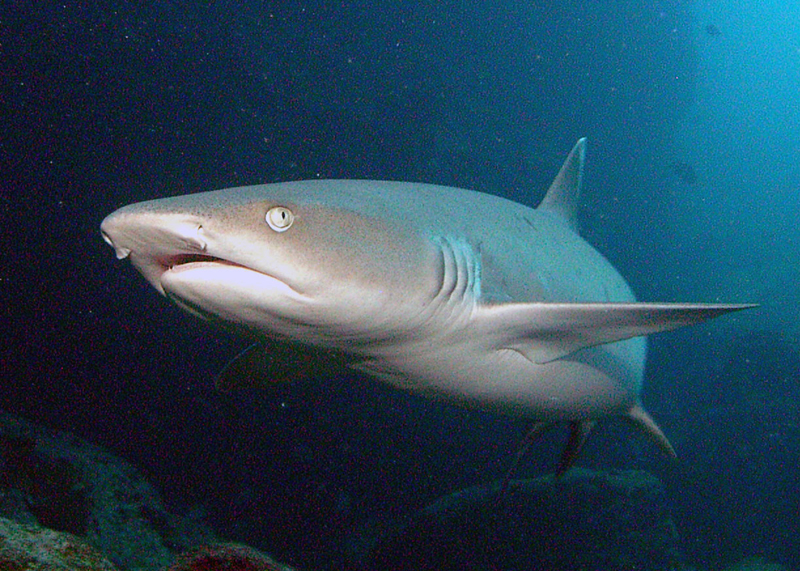

Jeepers creepers, where'd you get those peepers.

Being underwater all the time makes sight slightly less useful than it is in the crisp, clean (well, nowadays smoggy and filthy) air of landbound critters. Still, shark eyes are good, and (naturally) can see better underwater than a human’s. They can see you before you even know they’re there okay I’ll stop now. Anyways, shark eyes. The more durinal the shark is, the better its eyesight, the more nocturnal, the worse (harder to see at night and all that). Daytime active hunters tend towards the best eyesight. All sharks possess the tapetum lucidum, a reflective layer of tissue behind the eye that bounces light entering it back outwards, allowing improved night vision. Cats and dogs possess it as well – visible in cameras and at night as “eyeshine.” That’s right, shark eyes glow in the dark sorry I said I’d stop that. Many sharks possess a sort of eye-covering lid called the nictating membrane, which flips over their eye when they’re doing something that might hurt it, like mangling flailing prey. However, some, like the great white, don’t have this. Instead, to protect their vulnerable eyes when biting, they roll them back in their sockets, turning them from all-black to all-white (permission to shiver slightly granted) and relying on their other senses to land the kill.

Smell

Don't laugh; it works.

Ah, smell. The most famous shark ability, the ol’ “able to find a single drop of blood in an olympic swimming pool.” Truth be told, fish guts have always excited sharks more than blood under testing, but it’s still no exaggeration. Sharks have phenomenally keen noses, and that above swimming pool line is a fancy way of saying “one part blood per million seawater.” This nose leads them to prey over very large distances, as well as sewege outlets. Now you have one more reason not to swim near them – no need to thank me. By the way, the odd head shape of hammerheads, as seen above, is thought to provide a sort of extra platform for scent – making it very easy to determine smell direction by testing which nostril the scent is in, swinging the head back and forth as you swim. It’s also supposed to provide a broader platform for the Ampullae of Lorenzini, for much the same reasons – hammerheads are particularly adept at finding buried rays made completely invisible by hiding in the sand.

Lateral Line

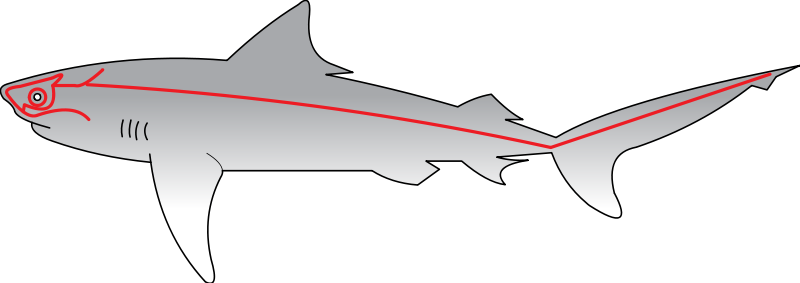

Note how line-like it is.

Yet another sense our feeble bodies don’t possess, but this one is scarcely unique to sharks – fish in general have it, as well as a few other marine organisms. The lateral line’s function can best be summed up as “ranged touch.” Groups of hair cells surrounded by jelly form “neuromasts,” which sense vibrations and movement in the water around them, arranged in, well, a lateral line down each side of the shark. They have a much longer sensory reach than the shark’s electroreception, and their hair cells bear a curious resemblence to those in the inner ear, hinting at a common origin. It might also let sharks tell if big chunks of low pressure – like say, a hurricane – is coming towards them.

I could mention taste and touch, so I will. The shark’s mouth tastes stuff, and also touches stuff, because the rest of the shark is covered in thorny dermal denticles (skin-teeth, or tiny little spiky bits that make a shark’s skin aquadynamic sandpaper). So if a great white grabs you in its mouth, it might just be seeing what the hell you are. You can’t fault curiosity.

- Credits:

- Drawing of electroreceptors in shark head: Public domain image from Wikipedia by Chris_huh.

- Whitetip reef shark: Public domain image from Wikipedia, from NOAA (U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration).

- Bigeye threasher: Public domain image from Wikipedia, from PIRO-NOAA Observer Program.

- Scalloped Hammerhead: Public domain image from Wikipedia by Littlegreenman.

- Diagram of shark’s lateral line: Public domain image from Wikipedia by Chris_huh.