This will hopefully be the final piece of cultural anthropology that I plop out onto this site, if only because I am frightened that my tutor will read it, pass out in horror, and then find and shoot me for my own good. As per always, plausible deniability, I was very young and stupid, it’s all a blur officer I honestly can’t say jesus christ I didn’t mean to hurt her yadda yadda yadda YADDA. And now we press on. Today we’ll cover various random things. You may now clasp your hands to either side of your face, bug your eyes out, and say “I had NO idea!” in an irrepressibly annoying voice. Go on. Tell them I said it was okay.

Politics: My Dong is Bigger Than Your Despot.

During the taking of this picture, Roosevelt expressed his desire for Stalin's hat.

Ah, politics. There are so many wonderful systems that humans have made whose primary tasks are convincing everybody that they are totally essential, but politics has to take the delicious, homemade strawberry angel cake with raspberries on top. Political anthropology is devoted to studying it; more precisely, things related to power. Who has power, who wants power, degrees of power, bases of power, abuses of power, excetera, etc, ec, e. Don’t confuse political anthropology with political science, however – political science is narrower in scope, dealing more with formal party politics, voting, and so on. Political anthropology includes that, a headman kicking someone out of the tribe for sleeping with his wife, and almost every leadership system outside of your family members telling you what to do. Now let’s get some of these here politimackul definitions. Because lord knows we didn’t cram enough into the last update.

-

Power: The ability to produce desired results by possession or use of force.

-

Politics: The use of organized public power.

-

Authority: The right for someone to take certain forms of action based on status or moral authority. Unlike power, you don’t need force to back it up. Notably, power doesn’t need this.

-

Influence: The ability to achieve an end through exertion of social or moral pressure on someone/some group, like your granny making you donate to charity or she’ll tell your mother about the enormous stack of porn she found in your closet. Unlike authority, you don’t need to be in charge or in center stage to exert this.

There we go, that wasn’t so bad. Now you’ve got a fascinatingly deep knowledge of politics rivalling that of the president of your nation’s nearest stamp collector’s club, and we’re ready to talk political organizations. We’ll be going roughly in order of appearance in human history, from earliest to latest.

Bands

Relatively eglatarian, sometimes nigh politics-free, and usually completely screwed.

The oldest human society of all, and one that some anthropologists have argued is politics-free in a pure state. Everybody’s pretty equal, leadership’s pretty informal, groups tend not to fight too much because they both don’t use up a whole lot, wander around a big area, and there aren’t many of them, and the closest you can get to politics is group decision-making. Usually you don’t have a big population growth rate because you get all your food via foraging and don’t build up big surpluses for population booms or specialists who don’t know how to feed themselves. Also, flowers and key lime pies rain from the skies on Tuesdays at six forty-five PM, so that you are well prepared for the 7 o’clock forced colonization and massacre at the hands of more complex societies (note that you cannot rearrange the letters in “complex” to equal “superior” or “better.” This means something).

Tribes

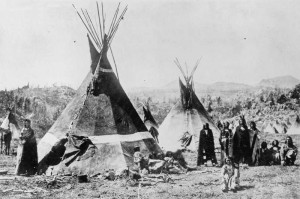

Once you’ve stopped foraging and started up planting and weeding (or herding and milking), you’re probably going to be in a tribal society. You’re a bunch of related bands held together in a territory by distinct language and lineage (and a dash of alliteration). A tribal headman is more certifiably “the boss” than a band leader, and he has more power, but he’s still part-time, and in charge because he’s respected – being generous earns a lot of respect. Since you’re starting to get a bit of food surplus, you can support the odd guy who can’t get his own food but is really good at making those specially carved statue-things you like so much, and maybe you’ll also be able to have more kids. Which is good, because the work you’re putting into growing/raising your meals is back-breaking, and you need all the extra hands you can get for weeding and tilling. Foraging was a free meal ticket compared to this.

Chiefdoms

A complex society can lead to all manner of hijinx, such as totem poles and lawn tennis.

Now we’re getting complicated. Chiefdoms are conglomerates of tribes and bands, all clumped together forever and ever under the chief. Society acquires more ranks and stratifications, and the chief may still acquire reputation through generosity but you better believe he’s going to be living a good bit better than the majority of his subjects. And make no mistake, they are his subjects now. This is no part-time leader, the chief has to take charge in major decisions and simply running the chiefdom. You can take this to the next level and have a whackuv chiefdoms linked together either under a sort of uber-chief, what you can call a confederacy.

States

Statehood is serious business.

Onward and upward into spiralling complexity. States arise as centralized political units, borne aloft on the flowery winds of intensive agriculture and storage techniques. Combining these technologies gives food surpluses out the sociological wazoo, and suddenly you have thousands of people free to take time off from feeding themselves to dedicate their lives to carving very large stone blocks, or charting the movements of the skies, or telling you that you need to kill those guys over the next hill or else your god(s) will be totally pissed off at you. It’s now relatively easy to get big cities rolling, or create a rigidly-organized religion, kick-start a technology, or launch a war. On the other hand you gobble resources like an emaciated hippopotamus, and you’re going to have to make sure that those other jerks in their state over the next hill don’t come over and take all your stuff, ideally by conquering them. Unless that would endanger your trade with them for those really shiny rocks your stoneworkers like so much. This is all a good example of exactly what states exemplify: complexity. They have eighty billion different benefits, issues, problems, and solutions, and often they all amount to exactly how well-coordinated the thing is.

Development Anthropology: Studying How People Will Screw Themselves This Time.

Development in action. Specifically, lung tumors.

Or, more specifically, studying how development changes cultures. Or how change develops them. Or whatever. Whether internal (finding a massive nickel mine ten miles from the capital, some random schmoe inventing the aromatherapeutic lightbulb) or external (a shipload full of conquistadors on your front porch, trading for a barrel of gunpowder and deciding to take a crack at deciphering it), change is inevitable. Thanks to globalization nowadays everybody’s in everyone’s backyard, and external influence is a given. How will nations develop? Modernize yourself with all the latest gadgets so you can play with the big boys? Fantically attempt to get your economy kickstarted enough that you can afford to feed more than 5% of your population? Try and reorganize things so that you don’t have that same 5% of your population eating 78% of all the resources? See if you can fix it so that everyone’s lives don’t really, really suck and are longer than that of the average fruit fly? Make sure that you aren’t eating up your next thousand years of resources over the next two decades? Everybody has a different goal, a different solution. Or the same goal with different solutions, or different goals using the same solutions. Whatever.

In the midst of all this, you’ve got institutions striving to help with development, or at least influence it. Two rough kinds: multilaterals (lots of nations as donors, such as the UN) or bilaterals (two countries, one giving, the other recieving). Naturally, the aid provided is going to vary depending on all manner of political bullhickory, and factors such as whether or not it’s meant to be spent on specific projects endorsed by the donors or untied to any specific goal, and whether it’s a grant or a loan. Anthropology comes into all this when an anthropologist is asked to advise on exactly what planting the Ultimate Power Dam Of Justice directly on top of a local village while ploughing over their burial grounds for a gas station might do to the area’s people. Originally this worked poorly, as the way projects were run basically went (1) create and design project with no input a thousand miles away, (2) ask anthropologist, (3) get pissed off when they tell you you’re a clueless berk. Nobody likes being called a clueless berk, and so anthropologists were disliked. Nowadays anthropologists tend to get more input into the situation, and have moved on a bit themselves from being consultants to actively monitoring their projects to make sure that nobody acts like a gigantic dick.

All of the above, interestingly, falls under applied anthropology, which is exactly what it sounds like: the application of anthropological knowledge to something, hopefully to better it. We’re seeing more and more of that nowadays, and some of it even works.

All original material copyright Jamie Proctor, 2009.

Picture Credits:

- Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt at the Teheran conference: Public domain image from Wikipedia.

- Shoshone around 1890ish: Public domain image from Wikipedia.

- Mayan pyramid at Coba: Public domain image from Wikipedia.

- Haida Houses around 1901: Public domain image from Wikipedia.

- World War II factory: Public domain image from oh for Christ’s sake just look up.