Or “marine reptiles,” if you must be so crude. Which you must. Really, I insist.

Marine reptiles are exactly what the label suggests, and since I’m fond of redundancy I’ll tell you: reptiles with watery habits living in watery habitats. Technically I’ve covered quite a few here already, such as your saltwater crocodiles and your sea snakes, and then there’s other stuff like your Galapagos marine iguanas and such. But you know what? They have the same problem all life currently present on earth does. Too small. Too petite, minute, tiny, eensy-weensy, itty-bitty. Too familiar. Too…..non-humongous.

But can it swallow a grown man whole?

So let’s look at some Mesozoic stuff! Who says the middle era is always the one the parents love the least, eh?

Truly, our era is impoverished of awesome.

Marine reptiles were a concept that had some potential in the Permian, but they became a boom industry sometime in the Triassic – which, I need not remind you, as I do so, is the first of the Mesozoic’s three periods. Some of the more notable groups that sprung up around this time include nothosaurs, which were possibly sort of a lizardy version of seals, going for fish and such, and placodonts, which were a sort of bulky mollusk-eating (“malacivores” – great word, isn’t it? Learn something every day…) bunch that started off looking kind of but not really like marine iguanas, found out what “predation” meant the harsh way, and ended up looking kind of but not really like sea turtles.

If these don’t seem that well known to you, that’s probably because they all died out at the end of the Triassic. Life’s mean that way. However, a contemporary of theirs did indeed make the cut: the ichthyosaurs. There are some scientific names you can accuse of being vaguely related at best to their subjects, but not these, not the “fish-lizards,” who were so devoted to reaching that perfect ideal of streamlined limblessness that they even developed live birth for it. They were elegant, they were sleek, and they’d already had a shot at growing grossly large by the end of the period (Shonisaurus was fifty feet long and swam in schools). They were also Stephen Jay Gould’s favourite example of convergent evolution – the development of similar biological structures for similar jobs by unrelated species; which in this case was “swim fast, find fish, chase fish, eat fish.” Sharks, swordfish, dolphins, ichthyosaurs…there are only so many quick-and-fast-hunter shapes available to be used in the water, although the customization takes over once the basic mould’s been set (a few ampullae of Lorenzini here, a long swordbill there, tendency to murder your own species’ young for amusement, maybe the phasing-out of teeth over time).

Think of them as dolphins, but with less Flipper. And thus, innately superior.

Ichthyosaurs went on to a long and prosperous history. They cleaned up in the Triassic marine reptiles sweepstakes, kept it going strong for most of the Jurassic, and then gradually petered out and expired towards the Late Cretaceous, cause unknown, which is, I’d like to say, a way no doubt we all wish we could go. By then, of course, they had competition, but they’d been coping with that for millions of years beforehand. Let’s look at some of that competition now.

Don't brag about your fishing rod unless it's built into your spine.

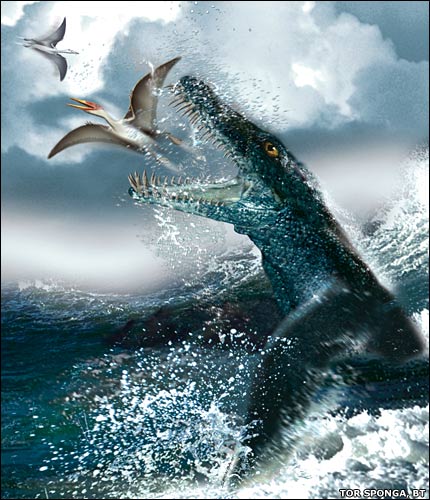

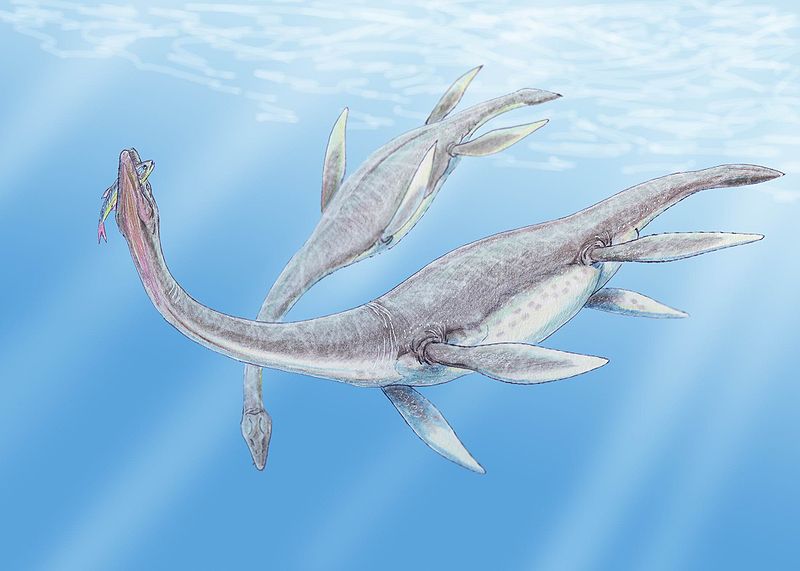

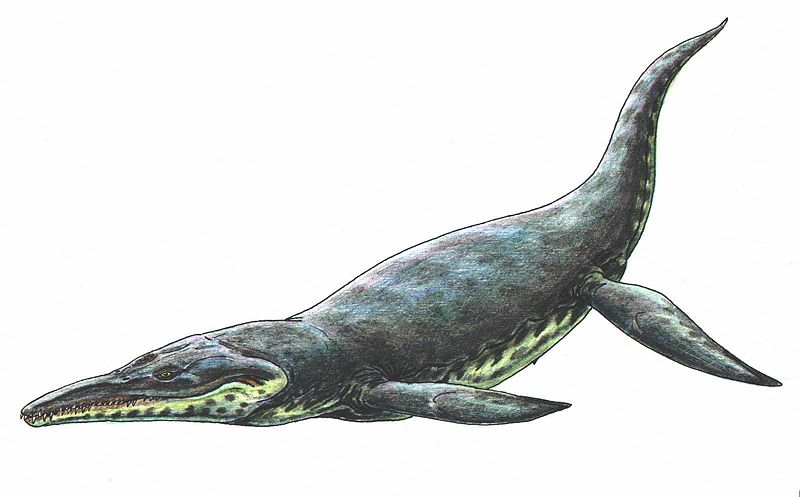

The next big ice-breakers on the scene were the plesiosaurs. Relatives of the nothosaurs, they escaped the fate of their cousins and started to throw their weight around come the Jurassic, popping up in the Early and getting bigger and better throughout the Middle to Late. Now, an important distinction must be made: plesiosaurs themselves were split into two groups: long-necked plesiosaurs, and short-necked pliosaurs, as seen below with our good buddy Kronosaurus.

Pictured above, a portion of the reason why sharks weren't the top predators during the Mesozoic.

The slower plesiosaurs were predominately fish-and-invertebrate-eaters, while the faster, heavy-jawed pliosaurs went after larger prey, including other marine reptiles. They were the super-orcas of their day, eating the things that ate everyone else and grinning all the while, with discoveries over the last few years being excavated in Svalbard exposing 50 foot+ monsters lurking out there. Incidentally, some unrelated triva: plesiosaurs are both an order (the above mentioned whole shebang of this group of marine reptiles), a superfamily (the plesiosaur half of the plesiosaur/pliosaur division), and a species (Plesiosaurus, a fairly generic 10-16 footish example of the prior groups). This isn’t confusing because science.

The plesiosaurs thrived right up until the Cretaceous extinction, when they abruptly vanished alongside most of the lifeforms on our planet that were actually interesting. Even after the icthyosaurs left them, however, they still had plenty of company. Roll tape!

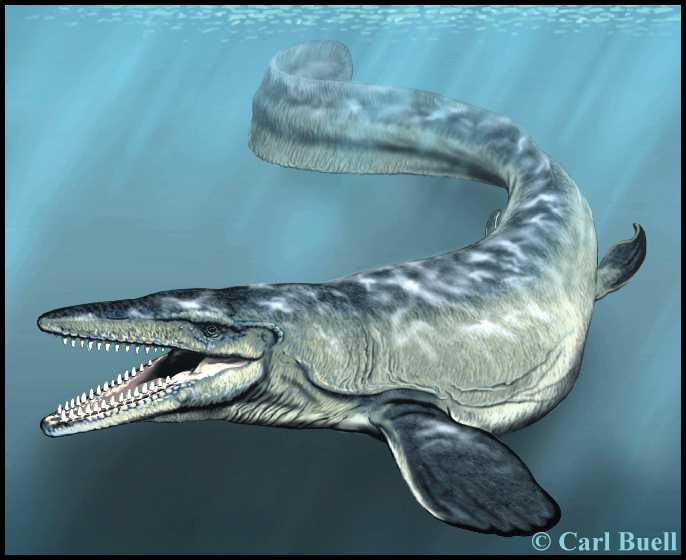

Why has no one written Moby-Dick with Mesozoic marine reptiles again?

Oh right, no videos. Whoops. The nice picture above shows Tylosaurus, among the lengthiest of all of the mosasaurs (50 or so feet, give or take a whistle), a group of marine reptiles whose closest living relatives today are probably snakes. They sprang up somewhere within spitting distance of the Middle Cretaceous, and despite their fashionable lateness they were soon swarming over the oceans like gangbusters, becoming the most prolific of all marine reptiles and the dominant predators de facto. They had at least 20 million years of glorious sea serpent-hood, their fins and elongated paddle-tails stretching boldly across the oceans, before they went out with the plesiosaurs. Alas and alackaday.

Odds and ends were still about, of course. Some crocodiles went for broke and became almost fully aquatic along the rim of the Triassic-Jurassic boundary, experimenting quite a ways into the latter period. Sea turtles popped up at some point, and have kept going on quietly and steadily in the face of absolutely everything and anything (so far…). But we have those already, sort of. And as any six-year-old knows, it’s what you don’t have that’s the most interesting. And as any sixty-year-old knows, it’s what you missed out on that’s always the most depressing. Poor us, over sixty-five million years too late to see a mosasaur eel past a dock. Poor us, forever having to make do with dolphins where we could see icthyosaurs gallavanting at the bow waves of ships. Poor us, for being robbed of the chance to see a giant pliosaur and a bull sperm whale go at each other flipper to flipper, jaw to jaw.

Ah well. Take what you can get. So listen up and save those whales, damnit – because they’re the next best thing we’ve got.

Picture Credits

- Marine Iguanas: Marine iguana from Philip Greenspun’s Weblog.

- Pliosaur: Drawn by Tor Sponga, BT, from BBC article:.http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7264856.stm.

- Nothosaur: Ceresiosaurus: Drawn by Dmitry Bogdanov, 2008, taken from Wikipedia.

- Placodus: Drawn by Dan Varner, found at http://www.oceansofkansas.com/placodnt.html.

- Icthyosaur: Platypterygius: Drawn by Dmitry Bogdanov, 2008, taken from Wikipedia.

- Pleisosaurus: Drawn by Dmitry Bogdanov, 2008, taken from Wikipedia.

- Kronosaurus: Public domain image from Wikipedia, May 9th 2007, by ДиБгд.

- Mosasaurus: Drawn by Carl Buell, found at http://www.oceansofkansas.com/mosa-sty.html.