Once upon a time, there was a lonely boy. His father was dead, his grandparents were dead, he had no brothers or sisters or aunts or uncles, and one day, his mother (who was a very powerful and much respected witch) died too.

Now, this boy was lonely, but he did not live alone. In his mother’s village, there were many who mourned for her, and who would have taken him in if he’d asked. But when he looked at the villagers, all he saw were the angry faces of the other little boys, the ones who made fun of him because they were jealous of his mother, who fought with him when the grown-ups weren’t looking.

So the lonely boy turned his back on his home, and he went travelling.

He walked to the far east, where he cut his way into the heart of a baobab tree and slept for three nights in it, drinking up its sap and its secrets in exchange for three headfulls of his dreams.

He walked to the far west, where he showed a hairy wild man how to shape blades to kill his kin, and learned the names and powers of every animal in the world.

He walked to the far north, where the world turned into sand and the air screamed insults that gnawed on his skin, and he learned the fiercest and most fiery curses in all the lands.

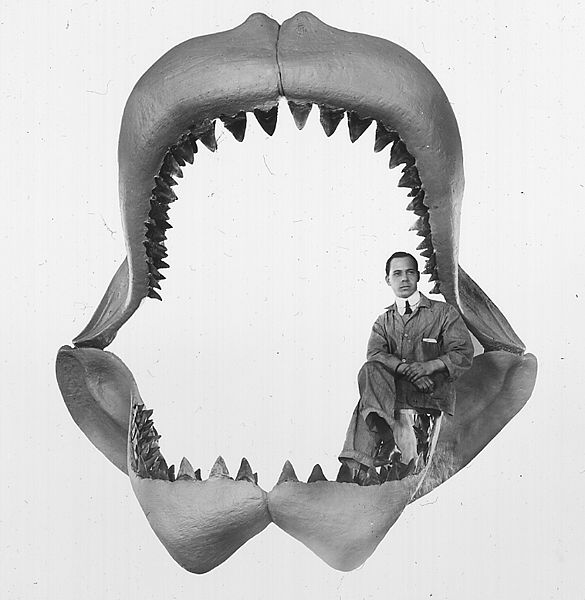

He walked to the far south, where the ocean slept in its bed, and after throwing three of his most favourite teeth into it he listened to all the whispers that came out of the oceans, and earned his new teeth from a shark.

He traveled, and he traded, and when he grew strong enough he simply took, seizing and grasping. He fought with a demon in the night in a wildfire and they each tore out the other’s eye – he put it in his socket and forced it to serve him. He stayed in a village and disrespected the chief, and when the people grew angry with him he ate their shadows and left them to wither away for years, ignoring their pleas. He forced spirits and ghosts to do as he pleased, and he hurt them when they begged to be let free.

By the time he came back to his home the lonely boy was an evil man, and a strong one, with arms that could uproot small trees and magic so strong that the air around him tasted like honey and iron. He walked into the center of town and he cursed the well dry, and he told them all that from that day on, they would do as he said.

Now. That was the end of that boy’s story – in a way, it wasn’t a boy’s story at all, not from the moment his mother died and he left home. But another one starts right here, right there.

This little boy had friends. Not many, but good enough. He had a family, a small one, but a pretty good one. Sure, his mama and his papa fought, but only with words and they never for keeps. He knew how people could be cruel, but also how they could be kind. Which was why it made him angry to see the magician as he hurt them; cursing anyone who dared to step across his shadow (which was three times as long as it should be) beating children who made fun of him behind his back (not that you could, with his stolen, blood-glowing eye watching all the time); and taking food and property from people without asking or bargaining, or drinking up their water in the middle of the driest time of the year. It made the little boy so mad that he mumbled words that his father used, and got smacked by his mother.

“Mind your tongue, little boy,” said his mother.

“She’s right,” said the little boy’s uncle, when he complained to him about it. They were outside the little boy’s house – uncle’s sister’s house – throwing small sharp wooden darts at a tree trunk, aiming for the knothole. Uncle was losing, as usual. “You’ve got to mind your tongue. You speak too fast and too free.”

“But it’s true,” said the little boy. “The magician really is an evil old” so and so.

The uncle bopped him, but lightly. “You listening? That sort of thing doesn’t help you any and it might hurt you. You really want to do something about this man?”

The little boy nodded so hard that his neck wobbled three ways.

The uncle gave him a thoughtful, feelful look. “That’s good. That’s right. You just need a plan then. You make the right plan, you can do anything. You got a plan?”

“I will kill him and throw him in the river,” said the little boy. Fwwt, his last dart sank into the knothole’s center.

The uncle sighed, and tossed aside his final dart carelessly. “That’s a goal. You want a plan. How you going to do this?”

The little boy thought. “I will fight him,” he said.

“Remember the last man that fought him? What happened to him?”

“Oh,” said the little boy.

“Look,” said the uncle, “he’s got magic, you’ll need magic. Here, I got a little bit left over from years back before, when his mother gave me a hand with something.” Uncle gave the little boy a smooth, shiny rock. It was a nice rock.

“This is a nice rock,” said the little boy, who could be polite when he tried.

“That it is,” said uncle. “Magic too. What you do with this is you take it in your hand – like so – and you hold it real tight – like so – and then you walk four times around your house thinking real hard – like so. Then you’ll have a plan. Got it?”

The little boy nodded, held the stone in his hand real tight, and walked around his house four times thinking real hard, then four times more, then four times more.

“I have a plan,” he told his uncle.

“That’s good,” said uncle. “What is it?”

“I will steal his eye,” said the little boy.

Now, the magician was standoffish by nature and necessity, and his home lay apart from the rest of the people, in the middle of a bare and burnt clearing. Four withered trees with four withered branches each were his guards, on each side of his home, and he slept with his demon eye open and awake, ready for intruders. Nobody ever went near that place.

“That’s a big job,” said uncle. “You got a plan for that too?”

“Yes,” said the little boy.

“That’s fine,” said the uncle. “You need help?”

The little boy thought it over. “Yes.”

“I’ll help then,” said the uncle.

“Thank you. The first thing we need, we need a dead cow.”

“Don’t think your papa would like us doing that.”

The little boy thought it over some more. “Then we need a dead antelope.”

So they went out there and got themselves a dead antelope. Uncle was a good hunter.

“The second thing we need,” said the little boy, “we need to lure out a lioness.”

So they went further out there and tied up the antelope and shooed off jackals and birds and all other pests, and then a lioness showed up.

“The third thing we need,” said the little boy, “we ask her for her lullaby.”

“This is some plan you’ve got here,” said uncle. “You sure it makes sense?”

“Yes,” said the little boy, so uncle nodded and asked the lioness, who was a bit surprised to see uncle pop up out of the grass like that. But they’d given her some food, so it was a fair trade, and she taught them all ten verses of her lullaby to her kittens, which was full of deep, throaty purring and blood and bones.

“Strong stuff,” said uncle. “I think I know what you’re up to. What’s next?”

“I don’t know,” said the little boy. “I can’t count past three yet.”

“Four’s next,” said uncle.

“Oh. Then fourth, we’re going to need a bone.” So they took one of the split leg bones of the antelope once the lioness had sucked out the marrow, and the little boy said they were ready.

“Now we just wait for sundown,” said the little boy. “And then I will go to the magician’s home alone.”

“You be careful, got it?” said uncle. “Your parents would skin me four times over if anything happened to you because of this.”

“I’ll be careful,” said the little boy. He walked all the way to the magician’s home, and by the time he got there it was pitch dark, too dark to see or do much but sleep. He took out that cracked, split marrow-bone and he squeezed and wiggled and snuck himself inside it – tight, but he managed. Then he started creeping up along the ground, inch inch inch, towards the magician’s door.

“Psst,” said the first, burnt tree. “Who’s that at my master’s door?”

“I’m just a bone,” said the little boy. “I’m doing no harm, I have no arms and legs to harm with.”

“That’s true,” said the first tree, “but if you want to come by, you’d better pay me a gift of some of your bonemeal. No free passage,” it said firmly, and scraped the dirt viciously with its four withered, charred branches.

The little boy didn’t have much choice, so he scratched and scraped away a bit of the bone with his knife until the tree was happy, then crept closer.

“Psst,” said the second, burnt tree. “What are you doing there?”

“Just a poor old bone, wanting to pass through, with no arms and legs to hurt anyone at all” said the little boy.

“I heard that,” said the tree, crossly. “But I want a gift too. If the others get bonemeal and I don’t, I’ll be smaller and weaker, and they’ll make fun of me.”

The little boy couldn’t refuse any of the trees, so he shaved and scraped and gnawed at the bone with his knife until there was almost no room for him to hide in it, and all four trees had been satisfied.

“Hang on,” said the fourth tree. “Did you say you have no arms and legs to harm with?”

“Yes,” said the little boy.

“Then what are those things peeping out from under your sides?”

The little boy rubbed his stone and imagined walking around his house four times.

“You’re seeing things,” he told the tree.

“I have no eyes,” it said.

“Then something must be really wrong,” he told it. “You should ask a doctor.”

“Oh no!” said the tree, and it was so busy wailing and mumbling to its friends while they cursed its noisiness that it didn’t notice the little boy sneak inside.

There, on his big bed that was as tall as the little boy standing, was the magician. He was sleeping cross-armed, legs straight, his one demon eye open and watching. Now and then he cursed in his sleep and the air in front of him burnt up and vanished.

The little boy crept up closer, right under his bed – he kept having to hold still and press himself into the cracks in the walls when the eye glared near him – and started to hum, then whistle, then sing the lioness’s lullaby. Bones and blood and sinew, crackling marrow, long dark nights and the smell of prey, all wrapped up in a big grumbling purr that tied a hug around your heart eight times over.

The demon eye blinked, yawned, and napped, lulled off to dreams of its hunting days, and then it started snoring. The little boy counted one, two, three, four snores, and then he leapt up, plucked it out, and ran out the door with his stone in one fist and the eye in another, too surprised for it to even yell. The trees were still arguing, and their four sets of four branches didn’t so much as pause from their slapping and punching at one another even as the little boy ran past right under their trunks.

“I have it, I have it!” called the little boy as he ran into his home, interrupting mama and papa from their talk with uncle about the sort of relative who let little boys run away in the night.

“Have what?” asked papa.

“The magician’s eyeball,” said the little boy. “Didn’t uncle say? Here, look.”

“No!” said uncle. “Don’t look! If it sees us, he sees us. Can’t let that thing take so much as a peek at anyone here.”

The eyeball was struggling pretty hard by now, so this was more difficult for the little boy than he thought it’d be at first.

“Here,” said mama, and she pulled out a big jug and they put the eye in there and shoved in a stopper, leaving it to curse and rattle and rail at them all it liked. None of it mattered; the eye couldn’t see them and they were safe.

“So, now what?” asked uncle.

“You don’t even have a plan?” asked mama.

“It’s not mine,” said uncle

The little boy took out his rock and walked around the house four times, then came back in.

“We need some salt,” he said.

They didn’t have much, but they had enough. A few handfuls. Papa opened the jar – pointed away from everyone’s faces, to be safe – and before the eye could start up its cursing again, the little boy asked it “how can we kill the magician?”

The eye said words that the little boy would’ve been thumped for. Mama dropped a pinch of salt into the jar.

“Aiieee!” said the eye.

“How can we kill the magician?” repeated the little boy. “You should know how, and you have no reason to help him.”

“I am his most faithful servant,” hissed the eye, with a voice like a snake caught between two sticks. “I am the only thing that lives that he very nearly trusts, and in return he does not harm me! There is not a single thing you can do that would hurt me as much as he could.”

Mama’s lips pursed a little at that, and she dropped in another bit of salt. The eye wailed like a lost hyena.

“Maybe we could put in ants next,” said the little boy.

“No!” shouted the eye.

“Or maybe a hungry spider,” said papa.

“Not that!”

Uncle scratched his beard. “Could try giving it to the dog, see what he makes it,” he said. “Been a good boy too, he deserves it.”

“Mercy!” begged the eye.

“Then tell us how to kill the magician,” said the little boy.

“You can’t,” said the eye.

“We could stab him with weapons,” said papa, “or hang him.”

“He knows the secrets of the plants and the stones and everything underroot,” the eye said. “They cannot harm him.”

“We could tie him up and leave him out on the plains at night,” said mama.

“He knows the names of every animal that lives there,” said the eye. “They will not harm him.”

“We could throw him in the river, like you said,” said uncle to the little boy.

“He has council of the oceans,” said the eye. “A little river shall not harm him.”

“What about fire?” said the little boy.

The eye thought. “Hah,” it said. “A good try, but that will fail too. At a single flick of his eye – his other, lesser eye – his shadow will wrap him up in its cold dark-bitten self. Not even the sun could scald him through that!”

For a moment there, no one knew what to say. So the little boy took his stone and walked around the house four times.

“Tell us how to stop the magician’s shadow,” he asked the eye.

“It is made from many, many, many shadows,” said the eye. “You must split it into pieces; how, I do not know. I have told you everything: now leave me be!”

“Right,” said uncle. He put the stopper back in the jar and gave it to the little boy. “Now what?”

The little boy took up his stone again, and started to walk around the house. One, two, three times, and then he had to hide behind a tree before he was finished, because the magician was walking up to the house, taller than papa and wider than uncle, single eye glaring and teeth showing in an angry snarl. His shadow was stretched out long, long, long behind him, and its hands were clenched into fists. The magician struck the house with the flat of his hand, and he yelled “Open up!”

The little boy heard nothing. Mama and papa were pretending they weren’t home.

“Come out now!” yelled the magician. “I know my eye was here – the thief’s tracks led this far. Come out now and bring me back my eye or I’ll eat all your shadows and curse your land into burnt crumbs! Open up!”

About then, uncle came back. He saw the magician up there in front of his sister’s house, and he knew what was going on.

“That’s my cousin’s cousin’s house,” said uncle. “What are you doing?”

The magician stomped over to uncle and glared down at him. “Your cousin’s cousin is a thief, and a scoundrel, and a leech, and I am going to sear him down to the spirit and then mangle it for my dinner. Where is he?”

“Gone hunting down by the river,” said uncle. “Been gone a week or more, the lazy man. A thief he is, and trouble for me and more than me. I’ll help you find where he is.”

“Good,” said the magician. “Show me where this lazy man is, and maybe I will let you live.”

So uncle walked off with the magician.

“He’s crazy,” said papa.

“Always,” said mama. “What are we going to do now?”

The little boy finished walking around the house once more, and even though his thoughts were a bit of a jumble, he made something up that seemed good to him.

“I know what to do,” he said. And he chased down the trail left by uncle, who had made a point of walking through mudpits and other damp places to leave good clear tracks.

The magician left no footprints, but here and there plants had been crushed and small things eaten by his shadow.

Down at the river – a good river, still flowing, even in the driest time of the year – uncle was leading the magician from fishing hole to fishing hole. “Not here. Not there. Not near, but where?”

The little boy watched and waited. He had a plan, and he hoped uncle did too. He hummed a bit of the lioness’s lullaby, as loud as he dared, and saw the magician look up and around with a start.

“Did you hear something?” he said.

“Just a lion,” uncle said casually. He looked very closely across the river and winked at the little boy, who was peering at him from between the rushes.

“I know every lion and lioness’s name,” said the magician. “And I do not know that lioness. Not properly. She sounds…muffled.”

“Maybe she’s sick,” said uncle. He was looking in the water, then back at the little boy, then waggling his eyebrows.

The little boy uncorked the jar with the eyeball in it and threw it into the water before it could scream. As it sank, fish swam to it, churning about the water.

“Look! See down there, in the water!” called uncle, pointing frantically at the swirl. “There, there, there! It’s my cousin’s cousin!”

“At the bottom of the stream?” asked the magician.

“One knows he’s a lazy, lazy man,” said uncle, raising an eyebrow across the river to no one in particular. “He only catches the fish that are two tired and old to bite bait, and just scoops them off the bottom of the pond three at a time. Laziness! Look, see here, you can see him in the water.”

The magician bent over to look into the pond, uncle yelled “FOUR!”, and the little boy threw his stone at the magician’s head. It bounced off with a clang, without so much as a dent, and vanished into the river, but it did what it had to do, which was put him off balance. The magician’s shadow lunged up into the air, peeling itself off the ground and ready to jump across the water, and then uncle shoved the wobbling magician off his feet and into the stream.

The eye had been right, of course. The waters parted around his lips and gave him breathing room, and he was swimming back to the surface with murder in his face quick as a blink. But his shadow could not swim, and it was dragged down after the magician and torn to pieces in the swift-shining currents, sending peels and dashes of smaller shadows everywhere that flittered away on the wind.

“RUN!” yelled uncle, and he and the little boy were off like shots, out into the dry long grasses by the time the magician had stepped onto the riverbank. But the magician was tall and strong and fast, and each of his steps was three of theirs, and he was driven on by mad hate now. There was no way they could outpace him.

“Hide,’ whispered the little boy, and they ducked into the grasses without a sound.

The magician came stomping up seconds later. His shadow was the size of a big man’s, and his one eye shone with nothing but sweat. He was tired and angry and he’d lost the trail of his prey, without his eye to watch and his shadows to lead, and he was furious.

Such a mood leads a man who was raised without attentive, admonishing relatives to words. Bad ones that made the air curl bright red and spark apart.

“Don’t say that,” said a voice to his right.

The magician whirled around and snarled at the bushes that had made the noise. They smoked.

“That either,” said something to his left. “Mind your tongue.”

The magician turned around again and yelled something that shredded apart half a grove of young acacias. A gazelle sprinted for cover.

“Don’t say that!” repeated the first voice, and a little wooden dart came zipping out of some grass that he was sure he’d cursed just a moment ago. It bounced off his head and made him wince. He screeched at the grass and it collapsed into hissing ashes.

“Carelessness!” said the second voice. “That isn’t helping and it might hurt someone!” Another dart, this one poking him in his good eye, setting him blinking and making his vision run watery. He yelled something really nasty at whatever he could see, and a shower of embers fell apart where stalks had sprouted.

“Stop it!” said the first voice, and it launched a dart right up the magician’s nose.

He swore and he stamped and he screamed and he bellowed and he let out a curse that caught the air on fire, fwoosh, and up went half the plains around him in flame. All around him, at the driest time of the year.

The magician ran, but you can’t outrun the wind. The magician roared, but you can’t outroar a fire. And the magician, and all his secrets, and all his bargains and threats and power all went up in a great sour cloud of smoke that hung low and sullen over the plains for four days before the rains came and washed it away.

Uncle and the little boy were all right. They’d run back to the stream, where they’d hidden beneath the surface as the smoke ran wild. And when they’d been nearly too weak to swim, who had held their heads above the water but the little shadows – their trips back home to their bodies delayed by the blaze, and thankful for deliverance? Mama and papa came down to the stream when the fire passed by, and dragged them home the rest of the way, where they forced them to eat until they left to go play darts again.

“That was a pretty good plan,” said uncle to the little boy.

“I thought it was yours,” he said.

Uncle shrugged. “Makes no difference. Want me to find you another rock?”

“No thank you,” said the little boy. “I don’t think I need it.”

“Good for you,” said uncle. “Now, beat that,” he said, and he threw a dart straight into the knothole.

The little boy said something and something else, and uncle smacked him on the ear.