Goodness gracious me, it has been a while since we’ve had one of these, hasn’t it? But with the second week in a row of total creative bankruptcy and general hopelessness upon me, it’s time I shared something else.

Let’s talk about our planet. It’s something like 4.54ish billion years old, and for an awful lot of its that it’s been very poorly-suited to life, what with oceans saturated with iron, often no oceans at all, an atmosphere that at one point was more methane than anything, and the distinct possibility of having turned into a single gigantic snowball on more than one occasion. It’s a little surprising that anything living would feel like taking a stab at reproduction on it; that’s the sort of optimism that our political system has carefully leached out of us.

But, as our history has shown, people need names to recognize things or they get all panicked and flopsweaty. So we’ve slapped various Greekish terms all over Earth’s various and irregular birthdays, comings-of-ages, and red-letter-days. If you sort our divisions of geological time from longest to shortest, we’ve got Eons, Eras, Periods, and then Epochs and Ages which no one really cares about. You don’t need to know epochs unless you’re into prehistoric mammals, and honestly, when you’ve got dinosaurs right there, why the hell would you do that thing? I wouldn’t.

So. We’re going to look at our planet’s history from beginning to end, with most emphasis on the bits where there’s slimy things with slimy legs crawling around furtively trying to mate with whatever holds still long enough.

The Hadean Eon

Named after the least cheerful and fun-loving afterlife in Greek mythology (such cheery terminology is also used in the naming of the hadopelagic zone, the deepest trenches of an ocean), the Hadean covers Earth’s history from its beginning to a little sooner than four billion years ago. There’s not much to say about it with regards to life because there wasn’t any; the planet was a bit of a hell-hole at the moment and although it begrudgingly managed to acquire a liquid ocean made from actual 100% water and an atmosphere of something like water vapour, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen, its heart really wasn’t in it. It idled. Rocks from this period are a bit of a bugger to find, and plate tectonics may or may not have been active something like four billion years ago.

The Archaen Eon

Archean, as in archaic, as in, “old, doddering, decrepit,” and stretching from a wheezy 3.8ish billion years ago (the abbreviation is “GA” if you must know, a shortform of giga-year) to a creaky 2.5 GA. This was around when life started turning up, somewhere in this mess – single-celled prokaryotic life (prokaryotic cells have no nucleus, leaving their DNA swinging about all willy-nilly within the cell). Apparently some amino acids formed up (not an unlikely thing at all to happen supposedly, given time and materials at hand), proteins popped up thanks to their meddling (not a likely thing at all to happen, given that amino acids need direction to make things and “just winging it” is unlikely to form a functional, properly socialized protein), and from then on it was a slide from protein-assembled RNA into DNA. Exactly how this happened is impossibly weird, over-debated, and half-known. Anyways, we’ve got fossils of stromatolites (big mats of photosynthesizing cyanobacteria) dating back about 3.5 GA, so there was definitely something in the water. Among other things, actually, the oceans were still saturated with iron, which was a bit of a pain in the ass – but that was all fixed in the

Proterozoic Eon.

“Early life.” Technically speaking, that would make the Archaen “earlier life” or maybe “earliest life,” but nits didn’t exist yet so there was small reason to pick at them. The Proterozoic stretched from 2.5 billion years ago to 542 million years ago, and it was around this time that the planet decided to try some harder life and came up with Eukaryotes, cells with nuclei to hold all their sweet, tender, DNA-giblets inside. We know for certain they were around by 1.4 GA, and they could’ve been first popping up as much as 2.7 GA, just before the end of the Archaen. Regardless of when they arrived, they needed something special and luscious to fuel their greedy little internal hordes of organelles (sort of the cellular version of organs – it’s believed that organelles had their origins in eukaryotes [which are rather large by cell standards] hoovering up prokaryotes and then decided to exist in peaceful symbiosis rather than absorbing them), and that something was oxygen.

If you can breath, thank your mother. If you're breathing in oxygen of your own free will, THANK A STROMATOLITE.

This had to wait for a little while despite the best efforts of the cyanobacteria: all that oxygen the new photosynthesizers were pumping out was going straight into the water and binding up with the iron, formed lovely alternating bands of rusted-red iron and black oxygen-poor iron in sediments all over the place by about 2.2 GA. Banded iron holds a hellacious amount of oxygen locked up inside it even today, and it was only once the oceans were nicely oxidized up that the atmosphere got its turn, becoming somewhat less stifling and more oxygenated about 2 GA. From then on, there was nowhere to go but up, and at some point or another, Eukaryotic life made a very silly move: it went multicellular. When you consider on the whole how much more numerous and successful most single-celled organisms are compared to us, it makes you wonder why it bothered, but then again, life itself is a case of needless complexity, and you can’t fault it for being consistent with its roots.

One specific period within the Proterozoic is quite noteworthy as far as life goes: the Ediacaran, the very last period of the very last era (the Neoproterozoic) of the Proterozoic proper. It lasted from about 635 mya to the 542 mya dawn of the Phanerozoic era, and it’s got a smattering of mysterious and soft-bodied fossils, of which practically the only ones that look anything like any life we know from anywhere else are jellyfish. The rest are strange by many standards, including most or all of ours. It’s pretty possible that this was an early attempt at life taking off at a sprint, one that was forestalled by one of those random disasters that wipes out almost everything that we’ve had an alarming number of times. But fear not! If there’s one thing life can be marked by, it’s its refusal to learn pessimism.

The Phanerozoic Eon

“Visible life” has been a work in progress from 542 mya to that ever-shifting little non-moment called “now.” As to its naming, if you can’t see a stromatolite with the naked eye, there’s something wrong with you. But this is the era where suddenly there was all kinds of stuff out there you could see without a microscope, and because of that, it’s time we got a little more detailed. Eras and periods will be all over the place here, and let’s begin by noting what is specifically NOT an era or period: the Precambrian. It’s a sort of blanket term that can be applied to everything before the Cambrian Period at the dawn of the Phanerozoic, the sort of geological equivalent to “B.C.” What noteworthy event could inspire such broad terminology? Let’s take a quick, misinformed peek.

The Paleozoic era

“Old life” opens up the Phanerozoic, and it does so with a bang.

The Cambrian Period

The Cambrian (RIP 542-488 mya, beloved by its children, named for the Latin term for Wales) is famous for the Cambrian explosion, as is only natural. Said explosion, to put it simply, was what happened when an awful lot of organisms decided (apparently overnight) that what they really, really, really needed was a shell. A phosphate shell, a silica shell, a carbonate shell, whatever. They wanted shells like we want a viable sustainable source of energy that will allow us all to continue to live in lives of gross excess, and suddenly the fossil record went ballistic. Soft-bodied organisms are much more difficult to preserve traces of than anything with a hard structure – look at sharks, their cartilaginous bones mean that most of the time the best we have to record them with is teeth – and the effect is a sort of explosion of life suddenly blossoming out of what seems to be nowhere.

If you want to see traces of the less-known, softer residents of the Cambrian, the Burgess Shale of BC, Canada, has a lovely record where some sort of extremely gentle landslide smothered an entire community (with love!) and preserved all its inhabitants with the perfection of a photo. Some of them are very, very, very, very, very weird.

By the way, trilobites turned up around this time. They were arthopods (insects, arachnids, crustaceans et al), diverse (17,000 species known, of various habits and inclinations), adorable if you found that sort of thing adorable, and remarkably long-lived, being the most ubiquitous and mascot-worthy inhabitants of the Paleozoic.

On land, not much was happening. Algae had cropped up on there about 600 mya, but nothing else was really going on. The Cambrian explosion was a marine club only.

The Ordovician Period

Named for a tribe of long-deceased Celtic yokels known as the Ordovics, the Ordovician lasted from 488-444 mya, and saw a few Cambrian developments thicken plottingly. The cephalopods began an intricate little burst of radiation and ascendance, jawless fish that had first crept onto the scene millions of years before began to experiment with making interesting shapes with their gill arches that could just barely be called “jaws.” The top predators were probably Nautiloids; shelled cephalopods.

The Silurian Period

Also named for welsh-based Celts, the Silures, the Silurian lasted from 444-416 mya, and was when several developments take off all at once. Jawed fish were proliferating, milipedes and scorpions made the trek onto land, and up there, waiting for them somewhat anxiously, were the first vascular plants – plants with structural support and internal vessels that slop around the various bits and pieces of nutrition and water they need. The first plants were seedless mosses and ferns, which did and still need moist places for their spores to mingle in water. Plant life wasn’t ruling the world yet, but it was spreading. Incidentally, why scorpions felt the need to leave the seas was a tad unknown, seeing as some of them were nine feet long and ruled the oceans with iron fists, claws, and mandibles.

Some of the earlier possibly-sharks show up right in the Silurian, and they definitely existed by 409 mya, right in

The Devonian Period

which lasted from 416-359 mya and broke the trend of naming periods after cultural subgroups that didn’t much care about geology except insofar as it pertained to woad, being instead named for an English county. Many things came to a head: fish rose up and took the oceans by storm with thirty-foot monsters like Dunkleosteus, which eschewed teeth in favour of gigantic, bony plates that it used as shears to bite directly through sharks and such (which, despite being the focus of such attention, were now pretty common). Stuff like this is why this is slanged as “the age of fishes.”

Possibly more strongly motivated to get the hell out of the ocean by now, some lobe-finned fishes decided to try their luck on land, and before the Devonian was over we had amphibians, the first tetrapods (four-limbed vertebrates). They still had to lay eggs in water, and stay moist, but they were up there and walking around, making life merry hell for the invertebrates that had gotten there first. Still, there was more livable land-space than ever before by the Devonian’s close; some clever plants (gymnosperms to their friends and acquaintances, if you please) had come up with the concept of sexual reproduction via seeds, creating little self-fueled packages that precluded the need for water. With these tools, plant life began to spread more quickly yet, and farther from water than before.

The Carboniferous Period

If you’re American, you could divide this period’s 359-318 mya body into the two chunks of Mississipian and Pensylvanian. If you’re anyone else you couldn’t care less and don’t really mind the period’s name, which, for once, isn’t even British-centric – “coal-bearing” is a pretty amiable and un-nationalistic title.

The Carboniferous saw plants really, really, really make it big. The seedless mosses and ferns had their last, greatest heyday, and swamps were everywhere. When plant matter drops into a swamp, it doesn’t rot – there’s too little oxygen in the water for most bacteria to break it up. Instead, it turns into peat. Leave peat for a few million whenevers, it turns to coal. LOTS of coal in the Carboniferous’s case.

With all those plants, oxygen levels hit what’s widely regarded as our personal planetary record. With that incentive, arthopods on land hit their own as well – since they absorb oxygen straight from the air, with no lungs, bug size is entirely restricted by how much oxygen they can sop up. We had two-and-a-half meter millipedes and dragonflies with wingspans of 75 centimeters waltzing around, and feasting on them were a cornucopia of amphibians, the most in history, along with strange little newfangled things called “reptiles.” They’d never catch on.

The Permian Period

By now (where “now” is 299-251 mya, and named cosmopolitanly enough after Russia’s Perm Krai) all the continents were in the midst of being crudely kludged together into one big lump: Pangaea, which would be complete before the period’s end. Inside it, stuffing its mass like jelly in a donut, were a gross quantity of deserts. Still, plant life forged onwards, and the first real trees popped up – conifers, gingkos, and cycads, mostly.

Reptiles, by now, had obviously caught on and were strutting about as if they owned the place. It turns out that once you cover your skin in scales, and your eggs in shells, you don’t really need water that badly anymore. And once you’re free from water, well, on a continent-of-continents with enough inland space to lose Russia like a set of car keys, there were a lot of opportunities for an ambitious little reptile.

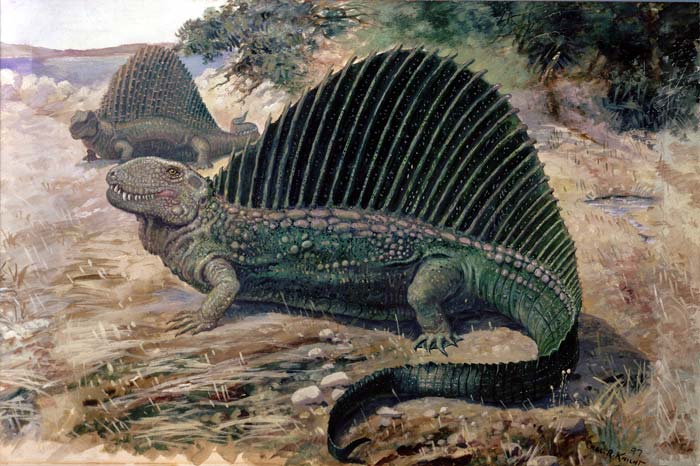

Mammal-like reptiles, or “therapsids” popped up around here too. Their most iconic if not notable member would be Dimetrodon, which is famously not a dinosaur at all.

The Permian ended, and so did the Paleozoic, the old life. But it didn’t end quietly. The era had begun with an explosion, and it closed on a somewhat different one: the largest mass extinction event of all time on Earth.

On land, 70% of all land species died. In the seas, the mortality rate was 90-95%. And that’s just species killed entirely; you don’t need that many individuals left alive to pull a species through an extinction event. It’s very possible that 99% of all living things died, all from who knows what. For all its impossible scale, the Permian extinction is too old and fragmented for many details to be pulled out, and no theories are solid enough to be confirmed. All you need to know, if you need one fact to judge its severity, is this: it is the only extinction event to include mass extinction of insects. That’s right; whatever this thing was, it was so harsh that the damned cockroaches had to live hand to mouth to pull through, and plenty of their relatives didn’t.

The casualties are innumerable, but the most prominent of all the deceased were that persistent, ever-scuttling emblematic class of the Paleozoic: the trilobites. After a little over two hundred and seventy million years, they had finally taken too much punishment, and the very last of them laid down their shells for the final time as the Mesozoic dawned.

The Mesozoic Era

“Middle life.” Also, you know, where you go when you want to find dinosaurs. Which most sensible people should.

The Triassic Period

At a nice even 250-200 mya duration, and a sensible, straightforward name originating from the triple layers identifying its formations in Germany, the Triassic was a neat, orderly fresh start after the near-brush with death that the entire planet had suffered at the Permian extinction. Life caught its breath, and then moved on, callously dumping many of the amphibians left over from the Permian as it went. Reptiles and therapsids took over (the former produced the world’s first flying vertebrates around this point: the fabulous pterosaurs, as well as the dolphin-esque icthyosaurs), and the therapsids pretty much enjoyed themselves at will until the mid-Triassic, where some strange little upstarts began to make themselves prominent.

Eoraptor, the "dawn hunter," and among the earliest known dinosaurs. The massive success of its descendants is attributed to early-bird hunting habits while therapsids slept in past noon.

They were called dinosaurs, and by the late Triassic they’d elbowed the therapsids out of dominance and into obscurity, where they and some very odd fuzzy milk-producing little things descended from them would remain until the Mesozoic’s end.

The Jurassic Period

Dinosaurs in the Triassic capped out in size at about the 30 feet of Plateosaurus, a prosauropod. Impressive, massive by today’s standards. They were just getting started.

The Jurassic (200-145 mya, and named after the Swiss Jura mountains, please and thank you) saw the rise of the sauropods (“lizard feet”), which had popped up either alongside or soon after the prosauropods, depending on whom you asked. They’re long-necked, long-tailed, and easily far and away the largest animals to ever walk on the planet’s surface – some of the more obscure and shadowy finds of the 20th century, based on singular, scary-huge bones, hint that their largest examples might have given blue whales more than a mere run for their money. As far as pure impossibility of body structure goes, few animals can match them; they’re built like living suspension bridges, and the specifics of the engineering required to run their circulatory systems, heat their bodies without boiling them, and move them around without crushing themselves are maybe just a little bit more than unbelievable.

While I'm admonishing people, as of 2009 Brachiosaurus as you most likely know it is technically "Giraffatitan." You see, the most complete specimen, the one they based all the artwork off, was in Africa, and it turns out it was a separate genus instead of a subspecies of Brachiosaurus, and hey pay attention hey.

As the sauropods grew, so did other dinosaurs. Stegosaurs arrived, plate-spined and spike-tailed, and all were hunted by larger and larger yet carnivorous therapods (“beast feet”), the most famous of which is probably Allosaurus, which may or may not have hunted in packs and may or may not have been ballsy enough to take on smaller sauropods in said packs (recent interesting speculation has been clustered around its bite habits: it shows a surprisingly weak bite for its size, but similar neck and jaw adaptations to sabre-tooth cats, which has led to the idea that perhaps it used its mouth somewhat like a hatchet, slashing and hacking to wear down big prey).

While all this exciting stuff was going on, a few smaller therapods had quietly taken to growing feathers – or at least growing more feathers; feathers themselves were distributed somewhat scatteredly around the therapod family tree, as insulation and decoration presumably – and jumping off things, then fluttering about. Archeopteryx (“ancient wing”) is the oldest known bird; toothed and tailed, with three sharp claws on its arms, it has come near to being mistaken for small dinosaurs several times. Well, that sentence is a bit misleading. Birds are small dinosaurs.

The dinosaurs weren’t the only creatures up to shenanigans. Salamanders evolved – quietly, like most things salamanders do – and the pleisiosaur family, which had first poked its extremely long necks out into the world in the Late Triassic, sidled into the spotlights. For easy pleisiosaur identification, if it has a long neck, it’s a pleisiosaur, if short and powerful-jawed, a pliosaur. Except recent rejiggering of the pleisiosaur family trees has dumped short-and-long-necked individuals in both groups, making separating them somewhat complicated. Between the pleisiosaurs, pliosaurs, and still-present icthyosaurs, marine reptiles were the word on the seas of the Jurassic. In the skies, pterosaurs held court, dominant and as of yet in blissful ignorance of the dinosaur’s casual preparation to horn in on their turf.

The Cretaceous Period

Pangaea had been splitting apart ever since the Triassic had seen it formed to its full extent, but it was pretty much fully divided by now (“now” being the period of 145-65 mya, and named for its lovely chalk), with groups of dinosaurs left in strange corners of the world to evolve like mad to their own desires. Sauropods still were in firm presence, though many of the older diplodocids and brachiosaurids had faded away in favour of titanosaurs like Argentinosaurus, which were every bit as enthusiastically large as their predecessors. The tyrannosaurs produced their largest member, the ceratopsians brushed the world liberally with horns, frills, and spikes, and the duckish-billed hadrosaurs spread like wildfire.

Now look, I know this isn't THE Tyrannosaurus, but Gorgosaurus was a perfectly respectable TyrannosaurID, and there's no call for you to make that face.

At sea, the icthyosaurs finally left the oceans, and in the Late Cretaceous the mosasaurs sprung up; most closely related to snakes or monitor lizards depending on who you asked. Whichever it was, they were more than eager to take the spot as apex predators, and did so with gusto. The skies saw their own regimes shaken: the birds spread and multiplied, the dinosaurs carving out their section of the air at the expense of the (somewhat annoyed) pterosaurs.

Everything was looking very pretty indeed when a very large meteorite slammed directly into the Yucatan peninsula, kicking up debris that clouded the sun for years, incinerating everything within hundreds of miles in a wave of heat and force, and generally ruining things. Among the casualties were the marine reptiles, the pterosaurs, the beautiful, coil-shelled ammonites so emblematic of the Mesozoic (leaving only the lonely nautilus as their surviving relative) and each and every last non-avian dinosaur. They’d lasted for 160 million years, substantially less than the trilobites, but with every bit as much breathtaking splendor. They’d taken the land, they’d started in on the skies, and if we’d given them a few more million years to play with I at least am damn well sure they’d have taken the oceans, lakes, and the whole bloody solar system.

This disastrous, massive extinction event was what finally gave our tiny, furry ancestors the kick in the tail they needed to poke their heads out of their burrows and consider doing something other than hiding for another two hundred million years.

The Cenozoic Era

Here comes the “new life,” same as the old life. But much smaller. And usually furrier. And always, always, always milkier.

The Paleogene Period

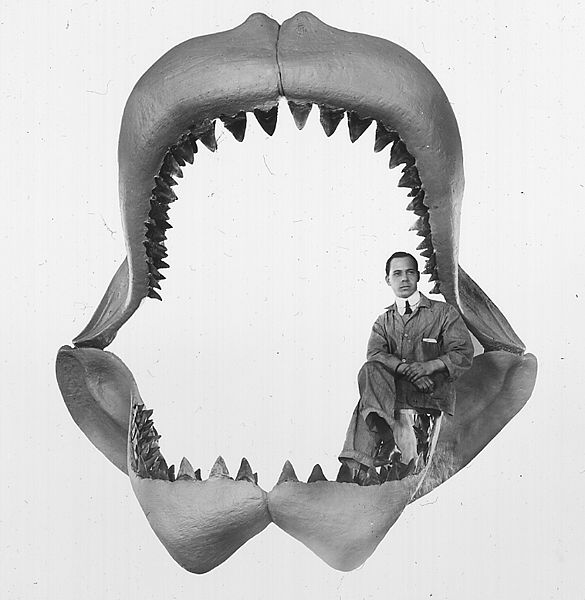

Covering 65-25 mya, this covers the bulk of the foundation of mammals upon earth. Whales cropped up around 50 mya, elephant ancestors somewhere similar. The oldest known primate is somewhere around 58 million years old, although the order’s roots could be back in the Cretaceous. The oldest, smallest ancestors of horses were skulking around forests somewhere. Somewhere around 28 mya, C. Megalodon (possible relative to the great white shark, probably fifty feet in length, definite eater of whales) popped up and made the oceans a very frighting place up until a mere one and a half million years ago.

The Neogene Period

25-2.5 mya, the Neogene was steady. If not much else. Look, horses were starting to look like horses and North and South America bumped uglies so a lot of species migration happened, what more d’you want from me? Alas, South America’s marsupials were the long-term losers of the Great American Interchange (so it’s called), and we lost the chance to have marsupial sabre-toothed “cats” in Ontario, more’s the pity. Opossums made it, though.

You ever noticed that the most survival-prone species are the unpleasant, omnivorous, nasty ones that have utterly no dignity? No offense.

The Quaternary Period

The Quaternary (fourth) period covers everything from 2.5 mya to today, and specifically the area of time in which vaguely hominidish things began to wander around Africa and consider smacking things with rocks (among objects considered: trees, sticks, bones, dirt, other rocks, other hominids). Most of the exciting and interesting megafauna died off within the last twenty thousand years – giant ground sloths that resembled tree sloths as much as chihuahuas do great danes; a rainbow of mammoths; glyptodon, which resembled a cross between an armadillo and an ankylosaur. As far as life on earth goes, the last couple of thousand years have been pretty puny in scale.

It is the period of time within which we can recognize the precise moment where everything went very wrong.

And it’s all your fault.

Picture Credits:

- Stromatolites: Public domain image from Wikipedia; Stromatolites, Zebra River Canyon Western Namibia, 12 December 2010, NimbusWeb.

- Trilobite: Public domain image from Wikipedia; Olenoides erratus from the Mt. Stephen Trilobite Beds (Middle Cambrian) near Field, British Columbia, Canada.; Photograph taken by Mark A. Wilson (Department of Geology, The College of Wooster), 6 August 2009.

- Silurian Fishes: Public domain image from Wikipedia; by Joseph Smit (1836-1929), from Nebula to Man, 1905 England.

- Dunkleosteus Skull: Dunkleosteus skull on display at the Queensland Museum, Brisbane (Southbank), Australia, photo: Cas Liber; 21 August 2006.

- Eryops Skeleton: Image from Wikipedia; Photo by Joshua Sherurcij, 2007.

- Dimetrodon: Public domain image from Wikipedia; 1897, Charles R. Knight.

- Eoraptor: Public domain image from Wikipedia; replica Eoraptor at Brussels Science Institute, submitted 2008, MWAK.

- Giraffatitan: Public domain image from Wikipedia; by ДиБгд, 9 May 2007.

- Gorgosaurus and Parasaurolophus: Public domain image from Wikipedia; by ДиБгд, 3 June 2007.

- Impact Event: Public domain image from Wikipedia; Made by Fredrik. Cloud texture from public domain NASA image, 18 May 2004.

- Megalodon Jaws: Public domain image from Wikipedia; Reconstruction by Bashford Dean in 1909.

- Opossum: Public domain image from Wikipedia; Johnruble 21 December 2006.

- Megatherium: Public domain image from Wikipedia; by ДиБгд, 22 July 2007.