Naturally, the vast majority of my 52 pages of notes proved useless, leading to me cursing once again at having been fooled into learning stuff without purpose. Now it’s demi-memorized and as such shall take an extra three months to leak out of my skull. The best use I think I can get out of this is to cram as much half-remembered misinterpretations of what I mindlessly stared at for two weeks into your heads as quickly as possible. Seatbelts on? Engine turned off and windows rolled up? Let’s get going.

The History of Cultural Anthropology (the truncated and demi-accurate collector’s gold limited premium special re-release edition with bonus discs and behind-the-scenes documentary)

Originally, of course, cultural anthropology didn’t exist. Why would you want to truly understand those other schmucks when that takes up valuable time you can use to kill them and take their stuff? Besides, they were obviously inferior, and therefore anything they could tell you would be worthless. They also didn’t believe in the right things, and should be properly brainwashed educated as to who was the biggest deity on the block.

Eventually the bad old days fell away and modern (well, early-to-mid-nineteenth-century) scholars began to conduct what is known as “armchair anthropology,” which basically followed a winning formula that I shall now bestow upon you:

- Send jackhole #092 into the wildes to communicate with the savages.

- Read ye olde reporte sent back by thine jackhole #092 (Day 1: met guye, Day 2: was fed by guye, Day 3: raped his wife, he got tetchy, shote him).

- Posit wanton and shamelessly second-hande speculations upon the nature of the savages described withine ye olde reporte.

- ????

- Profite.

Well, maybe not so winning as all that. Anyways, sooner or later someone realized they weren’t so much recording scientific information about other peoples so much as they were making shit up on the basis of a handful of scribbled notes, and this wasn’t really meeting the best standards of journalism, or even National Enquirer standards. So they hitched rides out into the world, arrived in the colonies, got to within a few miles of the nearest primitive tribes that just needed some white people’s direction, poor things, rolled up their sleeves, hitched up their suspenders, and lived in nice big houses. Once in a while they’d send word over to the chappies in the village that they’d rather like a native informant to come over to the place and have a nice chat on how him and his blokes did their thing, donchaknow. This was termed “verandah anthropology,” and it was an improvement in roughly the same manner as having cancer in remission is an improvement over cancer. Very much an improvement, but considering where you started, not saying much.

Well, around came World War I, or The Great War, or The War to End All Wars, three names for the same thing of which two are blatant lies – it certainly didn’t end wars, and it fails in both senses of “great” as not only was it pretty dismal but there was a bigger one right after it. During this period, a 30-year-old Polish man named Bronislaw Malinowski (a strongly excellent name, typed or said aloud) was waltzing about near New Guinea, a British-held domain. Australian authorities politely told him that as a Polish man from Austria-Hungary he was somewhat less than welcome to be at his leisure, and told him he could either get locked up or sit in the Trobriand Islands (what modern parents term a “time-out”). Bronislaw opted for the latter and conducted some of his most famous research, making advances in a new method of studying peoples: participant observation, which is pretty much what it sounds like. The anthropologist gets up close and personal with his subjects, finding out how they live by attempting to do it him(her)self. On the one hand you lose the verandah and become culturally incompetent to the point of children laughing at you, on the other hand you can actually connect to the people you’re studying as slightly more than “hey you, go get me a towel, some hot water, and a razor – chop chop!” and you get to actually learn something for once, since the more relatively normal you act the more relatively normal your study subjects will, too. Trading off pride and pomposity for contact and enlightenment started to appeal to more and more anthropologists, mostly because you came off as less of a twit and more of a scientist.

Speaking of scientists, Franz Boas may have done some stuff when we weren’t looking over the past few paragraphs. The “father” of American anthropology, Boas was German. Boas started with a doctorate in physics, moved on to geography, and spent 1883 with the Baffin Island Inuit examining how the local (and downright evil) geography affected their movements. He came out of it with a good deal of respect for the people and their culture, and an experience-backed attitude that anyone who presumed evolutionary superiority over other humans or their cultures was an ignorant tool. Over his life he played big daddy to anthropology in America, originated and encouraged the “four fields” method of divvying up anthropology that we went over last time, did stuff in all four, proved that anyone who argued for human intelligence based on cranial size was a moron, studied Native American languages like a man possessed, and promoted cultural relativism.

This man's moustache alone is smarter than either of us.

Okay, that was rather impressive. Well, actually a whole lot more than rather. Now that we’re done remembering how much more energetic everyone seemed to be about a hundred years ago, let’s stop reviewing the past and look at the present.

What the Hell are You Doing?

Now, there are quite a few ways of getting your info on whoever you’re staring slightly too closely at this week on-site. Because we are full of SCIENCE we shall have a special term for each of them, which I shall convey to you through the magic of crude description.

- Etic research refers to the gathering of data and juicy gossip by outsiders looking in on a culture and checking in on specific questions.

- Emic research refers to descriptive reports of what it’s like living in Insert Subject’s Hometown Here conveyed by insiders about their culture.

- Deductive research involves asking a question or posing a hypothesis and then gathering a bunch of info, then figuring out whether or not you’ve proved, disproved, or haven’t the foggiest about your original idea.

- Inductive research involves gathering a bunch of info and then seeing what it tells you. “Screw the hypothesis, I have data” basically.

There, who says definitions aren’t fun? Look at how much fun we just had! By the way, the data constantly harped upon above can come in two broad flavours

- Quantative information come in the form of charts, graphs, tables, and numbers. Lots of numbers. No, more than that. You will count those numbers up and you shall like it.

- Qualitative methods rely on written descriptions, reports, and so on. No (well, not as much) counting, but lots of talking. And scribbling.

Both require participant observation to pull off, observation skills technically described as “out the wazoo,” and reliable methods of recording said wazoo-related eruptions of data, all with sides of both up and down. Written notes can be really comprehensive and jotted down right as the event happens, or they can be limited by writing speed or taken later when the memories have had time not only to degrade but to actually drop out of school and get really high, in something like that order. Tape recordings can grab all the sound in an area, being at once incredibly informative and incredibly irritating at a single stroke (boy, bet you wish you hadn’t sat next to the instruments when that guy was making the big, important, once-a-year speech, eh?). Video cameras, well, we need not chat about how much they can snag, but they only really get what you point them at. Tons of little details that you might catch on and note yourself can get gleaned over in a video, particularly if its quality is what the polite people call “crap.”

Oh, and while we’re at it, there’s a few distinct ways to have at your research. Because lord knows we can’t have enough definitions.

- Ethnography. Exactly what it says, “culture writing.” You write about a culture. Specifically, you write up all your info into a honkin’ big pile of words on the culture. It’s descriptive, detailed, and first-hand. You can write it in a traditionally detached third-person manner (realist ethnography, the traditional method), or you can get really fancy and use a more recent approach known as “realist ethnography,” where it’s first-person, poetical insight may be used, and you aren’t afraid to liberally sprinkle “I” through your writing. I think that sounds more like writing a book than a research document, but bear in mind that I’m a flamin’ idiot.

- Ethnology. Cross-cultural analysis, which, again, is basically what it’s called – you take a topic, say, the particular noises that people consider polite to make when eating something at lunch in public, and then you compare how different cultures do it using ethnographic materials. You check out what’s similar, what’s different, and why they might be alike/not alike.

Final thing for today – recall our little lesson on ethnocentrism yesterdayweek? Remember how I mentioned that it was dumb, and stupid, and smelly, and only a total jerk would use it, and I was all like “hey, you shouldn’t judge other people’s arbitrary crap by the standards of your arbitrary crap”? Scroll upwards to check out the lattermost of the eminent Franz Boas’s achievements: promoting cultural relativism. That’s it. Cultural relativism: the denial of judging other cultures by your standards, and the opposite of ethnocentrism. And then I was “but that doesn’t mean you can claim genocide as a cultural tradition and say that makes it okay”? That’s one of two really vague “flavours” (I use that term too much. Let’s try “sounds” next time) of cultural relativism: absolute cultural relativism (the aforementioned “I cannot judge your decision to eat your baby because it vexes you/preach that the heathens must be shot until they worship the right imaginary friend”), and critical cultural relativism (“Both of those sound like bad things for everyone”). The prior is widely regarded as being quite dense by absolutely everyone, the second as being preferable to either ethnocentrism or its own moronic sibling yet philisophically difficult to justify. Then again, philosophy makes many things difficult to justify, so let’s do what almost all people do when confronted with philosophy: ignore it because it makes your head hurt.

I promise that next time I shall chose a topic that lends itself more favourably towards purty pictures.

All original material copyright Jamie Proctor, 2009.

Picture Credits:

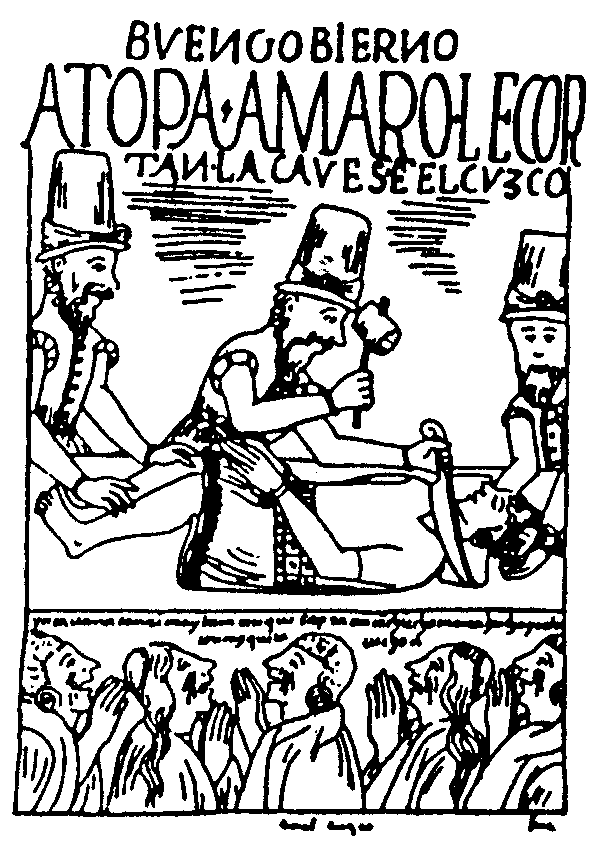

Tupac Amaru being shown who’s boss by Spaniards in 1572: Public domain image from Wikipedia.

“The Rhodes Colossus” from Punch in 1892: Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Franz Boas being awesome in 1915: Public domain image from Wikipedia.